US Gun Violence; Canada’s; BC’s Fugitive Methane Emissions and u.s.

There's a big difference between gun violence rates in the United States and Canada -- and in the fugitive methane emissions rate in the US and British Columbia, too.

There’s a big difference between gun violence rates in the United States and Canada – a factor of 7, according to a recent article from NPR based on 2021 data. [4.31 gun violence deaths per 100,000 people per year in the US; 0.57 in Canada.]

There are several reasons for this factor-of-7 difference. Effective gun regulation is one of them. Lessons? Regulation matters, so it would be wrong to project United States gun death rates onto Canada.

So, let’s turn to fugitive methane emissions. That’s the formal term for any gas that leaks into the atmosphere during natural gas production, distribution and end use. Methane, the main component of natural gas, is itself a potent greenhouse gas, so we want to keep these fugitive emissions to a minimum. Natural gas causes enough warming when it’s combusted into carbon dioxide, after all.

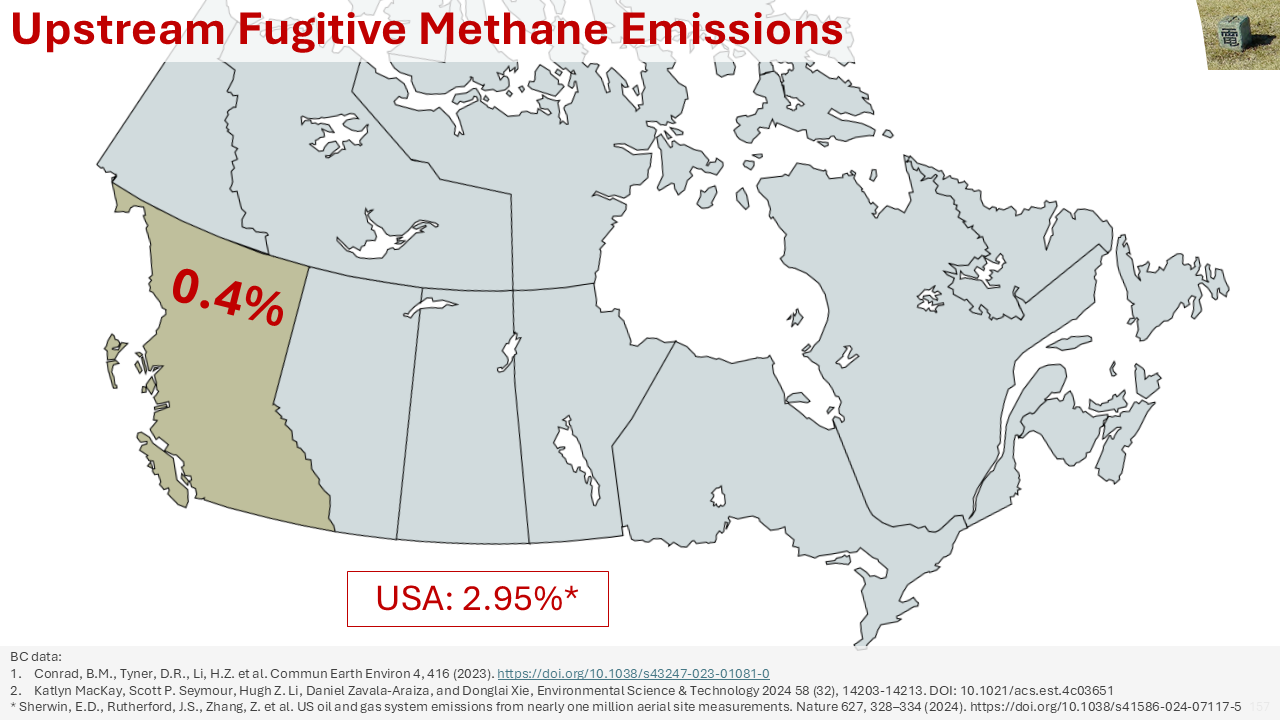

Based on about a million site measurements, Stanford-affiliated Sherwin et al recently estimated that upstream fugitive methane emissions from US natural gas wells amounted to 2.95 percent of production. With America’s current political climate, stricter regulations may not come for some time.

For British Columbia – which has recently started exporting liquified natural gas (LNG) – two papers encompassing three datasets both estimated upstream fugitive methane emissions to be about 0.4 percent. [Carleton + EDF in 2023, EDF solo in 2024.]

Our friend the factor-of-7 difference reappears. [2.95 percent vs 0.4 percent]

By now, that’s an understatement. Thanks to stringent regulations, BC’s fugitive methane emissions rates will have fallen further since those datasets were compiled, as noted by a Pembina Institute study last month. Still more work needs to be done, of course, and we still need to transition to non-fossil fuel gas energy, preferably sooner than later.

Fugitive Emissions: Industry Edition

Historically, fugitive methane emissions were one of the “known unknowns” of natural gas production. It was known leaks happened, but no one bothered to improve things, because that’s just how things had always been done. There was no grand [fossil fuel industry] conspiracy at work, it was just assumed to be an inevitable part of doing business, so generation after generation of workmen did things the same way.

That changed about 15 years ago, raising concerns whether natural gas’s global warming effect might be worse than coal on a 20- or even 100-year basis. Often forgotten is the fact that coal production comes with its own fugitive methane emissions. Gas leaks leading to explosions are a big reason underground coal mining is so dangerous!

In 2023 an RMI (Rocky Mountain Institute) affiliated study estimated that for natural gas to be as bad as coal on a global warming basis on a 20-year timespan, methane leakage would have to be 4.7 percent. On a 100-year timespan, it would have to be 7.6 percent. (These are broad averages of course, with much variation on a case-by-case basis.)

Those lifecycle percentages aren’t directly comparable to the 0.4 percent cited for BC above, because the BC figure is only for upstream emissions: emissions relating to production. A small amount of leakage occurs during transmission (pipeline transport), distribution (gas pipes criss-crossing your town) and end use (leaky stoves, etc.). Even so, it would take acrobatic math to argue BC’s natural gas will be worse than coal on a 20-year basis, let alone a 100-year basis – even if it’s turned into LNG and shipped overseas.

Not that BC’s LNG industry will be huge. We’re a high cost producer; we won’t be minting zillionaires. And we’re further from most customers than most competitors. BC will be to LNG what Subaru is to [combustion-era] cars: a small player with a particular niche.

Is LNG one of my preferred industries? No. Will it have a fifty-year ascending arc like renewables? Also no. Do I have the hubris of an economically secure, university educated, white collar, professional managerial class urbanite who hectors less-prosperous rural areas to reject economic development? Hell no. That strategy may win donors – but it loses elections.

I side with New York City Democratic mayoral primary winner Zohran Mamdani when he says, “a life of dignity should not be reserved for a fortunate few”. There’s neither dignity nor victory in a message of, “I know half the forestry jobs have disappeared since 2000, but you need to wait until the industries I approve of, start to scale up”. That’s a powerfully losing message. No amount of rhetorical yoga can save that message.

We won’t win by saying “no” to every fossil fuel project. We’ll win by saying “yes” to so many clean and renewable energy projects – at every point across the province – that well-paid workers and well-off communities can afford to be as picky as economically secure, university educated, white collar, professional managerial class urbanites are.

Back to timeframes, I can see the narrow value of using the 20-year calculations to advocate for stronger fugitive emissions regulations. But criticizing natural gas because, when produced in the unregulated dystopia of the United States – it might “only” better than coal on a 100-year, 50-year and 21-year basis – well, that’s a strange pose. “It’s better over the long term” is a feature, not a bug.

A popular slogan during the Quebec sovereignty referendum thirty years ago was, “my Canada includes Quebec”. Well, my Canada includes 2046 (21 years from now), 2075 (50 years), 2125 (100 years), and beyond. I’ll still co-sign petitions to reduce methane leakage. I want BC’s natural gas and LNG to be better than coal over 10-year, 3-year and 1-year timeframes – and the natural gas is probably close already.

I’ve explained how the fugitive methane emissions rate for US natural gas and BC’s, are as different as gun death rates in America and Canada. Between firm regulations and watchful non-profits, I want them to be as different as gun death rates in America and Japan.

Whither Seven Generations?

Now, there is another reason I’m committed to the 100-year timeframe. It might not apply for younger readers, but it will for many in my age bracket.

I’ve spent decades in private conversation – and probably the public record – attesting to the wisdom of Indigenous “Seven Generation” thinking. People have children later in life these days, so seven generations is about 200 years, but we can use 100 years as a proxy. Whether you prefer 100 or 200 years, on a Seven Generations basis, LNG’s global warming impact will be lower than coal’s – unless it’s produced in Dickensian kakistocracies whose industry practices and equipment never improve over time. Natural gas’s impact will be considerably lower. Focusing on the 20-year timeframe? That’s One Generation thinking.

One desultory cycle in Canadian history has been the loop of westerners talking a good game to Indigenous Peoples – then reneging on promises, commitments and treaties the moment they’re inconvenient. I affirmed long-term, Seven Generations thinking with sincerity. I talked that talk. I’m going to walk that walk.

Apart from the narrow purpose of galvanizing regulations, I’m not moving the gas-versus-coal goalposts to 20 years because some fellow westerners now want to think shorter term. What’s going to happen? First Nations who benefit from – or may soon co-own – LNG projects are going to call them out. “What happened to decades of talking up Seven Generation thinking? Now you’ve decided One Generation thinking is more convenient. How is that allyship?”

The 20 year timeframe remains narrowly useful to galvanize regulations to reduce fugitive emissions; for all other purposes the Seven Generations-aligned 100-year timeframe should take precedence.

Fugitive Emissions: Household Edition

Humour is a useful lubricant for difficult conversations. Hence court jesters being the only ones who could tell kings hard truths.

So, I want to talk about how fugitive methane emissions are the male-pattern urine splatter of the gas industry.

Well before indoor plumbing, it was known that male-pattern urine splatter happened – but no one bothered to improve things, because that’s just how it had always been done. There was no grand conspiracy [of the patriarchy] at work, it was just assumed to be an inevitable part of doing [one’s personal] business, so generation and after generation of men [emptied their bladders] that same way.

Robert Howarth is the Cornell professor who brought the issue of fugitive emissions from natural gas into prominence about 15 years ago. Well, call me the Robert Howarth of urine splatter, for doing the same right now...!

The good news is that, just as fairly simple practices can all but eliminate fugitive emissions from natural gas production, one simple practice can all but eliminate male-pattern urine splatter: “sitting”.

In this practice, the buttocks and haunches create a barrier that prevents practically all rebounding droplets from venting to atmosphere, landing on exterior surfaces and smelling badly. The differences in volume-of-splatter are probably on par with American vs Japanese gun crime levels.

But there’s more! A surprising proportion of methane emissions come from a small number of super-emitting gas wells. I swear to Gaia, it only takes a few guys with terrible aim to make the sports stadium men’s washroom experience go from Bad to Even Worse.

Now, some climate-inclined men are going to be annoyed at being told to improve their bathroom practices out of consideration for others. They’re like the gas industry roughnecks annoyed at being told to improve their gas well practices out of [climate] consideration for others. I’m no expert at poker hands, but I bet “happy wife, happy life” beats “real men pee standing up”.

[If any women readers are actually able to convince their male partners to upgrade their bladder practices based on this article, please let me know. It’ll restore a bit of my faith in my half of the human community.]

Of course, the big differences between the oil and gas industry’s fugitive methane emissions and individuals’ urine splatter are their scale and impact on global warming. Sherwin’s previously mentioned paper estimated these methane emissions in America amounted to more than 6 million US tons per year (publicly accessible write-up here). That’s equivalent to more than 160 million metric tonnes of CO2 (on a Seven Generations, 100 year basis).[1]

The oil and gas industry not paying attention to methane leakage, decade after decade – well, that’s an asteroid sized blind spot. More leadership diversity might have caught and stopped this earlier. We all individually have big blind spots – I sure didn’t think about urine splatter before getting married – and if organizations’ leaders are too alike, everyone’s big blind spots will line up. And asteroids will get through.

The only way to solve this is with diversity.

It’s not just a matter of diversity for mercenary corporations or industries, either. There have been big blind spots even among environmental non-profits, which have unintentionally caused pollution and suffering on only slightly smaller scales.

We’ll look at that next time, in “The Sierra Club (of 1972) versus the Black Panthers”.

Let me be spotlessly clear that I’m not referring to the Sierra Club of today. I agree with them on many, if not most, issues. I’ll be talking about the Sierra Club of yesteryear (yester-decade?).

Thinking the Sierra Club of the 1970s reflects the Sierra Club of today would be as illegitimate as … thinking US fugitive methane emissions rates apply to British Columbia’s natural gas.

[Post-script: it appears US states are trying to say natural gas plants should qualify for green tax credits. This is like the Emperor Caligula making his horse a Senator – except that story was made up, and this is somehow happening in the real world. I’ll co-sign petitions against that as well.]

[1] That’s based on fossil fuel methane’s GWP, or global warming potential, of 29.8 multiplied by those aforementioned more than 6 million tons. Then correcting for the fact that 1 metric tonne equals 1.1 US tons