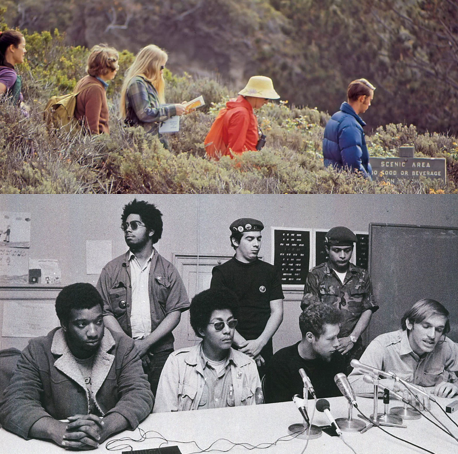

The Sierra Club (of 1972) vs the Black Panthers

“We protected the world from nuclear power” rings differently than “we protected the world from nuclear power, and in retrospect it cost the health of a hundred communities poorer than ours”.

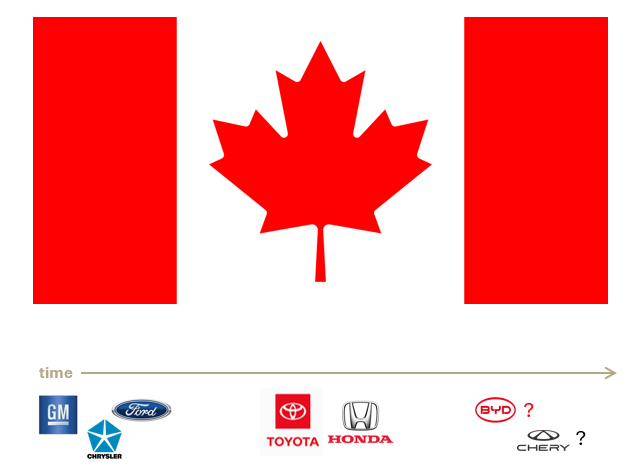

Last time I wrote about how upstream fugitive methane emissions rates (leakage per unit of natural gas, basically) from British Columbia’s natural gas production are about 1/7 the level in the United States – like how Canada’s gun death rates are about 1/7 as America’s. I hope it’s readers’ “number 1” most memorable essay on fugitive methane emissions.

I made my argument for using 100 year timeframes when talking natural gas and coal – reserving 20 year timeframes for the narrow purpose of galvanizing regulations to reduce fugitive emissions. I’d like BC’s (and eventually Canada’s) leakage rates to be as different from America’s, as Japanese gun violence rates are, from the US’s. And for US fugitive emissions rates themselves to come down too.

I also argued that fugitive emissions, among other examples, weren’t a grand conspiracy but a mundane case of people doing things as they’d done before, decade after decade, with an asteroid-sized collective blind spot around improving things. I explained that I thought this has historically affected environmental non-profits too – but that judging today’s non-profits by 50-year-ago practices would be like judging BC’s fugitive methane emissions by US ones.

Today I want to cover the Black Panthers, nuclear power, and the Sierra Club of 1972. (As distinct from the Sierra Club of today.)

The Black Panthers: Klipp Notes

You may know the Black Panthers – the iconic African American community empowerment group – as maybe the only community organization to make the NRA (National Rifle Association) run to government asking for more gun control. For certain groups. [Details on the Mulford Act can be read here.]

That’s a pity, because the Illinois chapter of the Black Panthers – under early leader Fred Hampton – worked a political miracle. They created the first “Rainbow Coalition” to advance class-based politics on behalf of the urban poor.

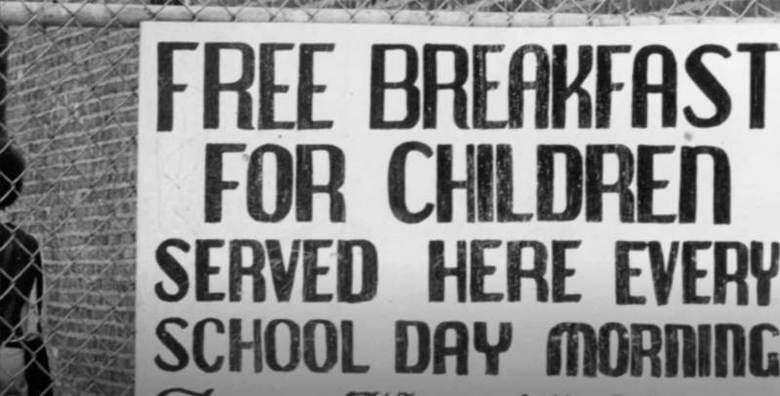

We don’t know the peaks they could have reached, because a few months after an informant told the FBI the Black Panthers mainly served free breakfasts for poor schoolchildren (20,000 schoolchildren across the country) an unarmed, asleep Hampton was “unalived” by law enforcement, who sprayed 90+ bullets into his apartment. You may be reminded of that other non-Caucasian fellow who worked miracles, served the poor, fed thousands, got betrayed and was then “unalived” by the Roman Imperial state apparatus.

The Rainbow Coalition was formed in Chicago in 1969, and brought together the Black Panthers, serving the marginalized African American community; the Young Lords, a similar group serving the also-marginalized Latine community; and the Young Patriots, a similar group serving the also-also-marginalized white working poor arrivals from the American South. The quid pro quo was that the Young Patriots could keep using the Confederate flag as a heritage symbol – if they condemned racism.

What kinds of challenges did Rainbow Coalition communities face? Let me quote from this NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council) webpage (my emphasis):

“[Environmental racism is] … the intentional siting of polluting and waste facilities in communities primarily populated by African Americans, Latines, Indigenous People, Asian American and Pacific Islanders, migrant farmworkers, and low-income workers.”

Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis Jr., who coined the phrase “environmental racism”, also included among its evils, “…the history of excluding people of colour from leadership of the ecology movements”.

Credit to Ecojustice for including that latter part. Not all non-profits do. I’m sure I disagree with them on a lot of issues, but you learn the most from principled people who think differently from you.

Yesteryear’s Anti-Nuclear Campaigns

I think we all have the lived experience of seeing (or being) people shaped by traumatic experiences. There will have been many reasons for the anti-nuclear campaigns of the 1970s and onwards; I’m sure the traumatic experience of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis was one of them.

If you spent that October terrified the world would end in a nuclear apocalypse – the US and USSR each detonated nuclear bombs during the crisis [see the Wikipedia page for nuclear weapons tests] – you might develop a lifelong phobia around all things nuclear. All the safety statistics in the world (nuclear power is extremely safe) wouldn’t change your mind if you, or perhaps a mentor, had that traumatic, life-altering experience.

Hydroelectricity is the best counterexample. The overwhelming majority of people accept hydroelectricity, and statistically, it’s almost as safe as nuclear. But if you lived through China’s Banqiao Dam disaster in 1975, which killed somewhere between 26,000 and potentially 240,000 people, you might have a lifelong opposition to hydroelectric power. On the high end, that’s as many deaths as Hiroshima and Nagasaki, combined. And Hiroshima and Nagasaki were nuclear bombs, not nuclear power plants.

Whether we support hydroelectricity and/or nuclear power projects, we can’t look down on opponents because they had a traumatic experience and we didn’t. In one domain or another, we’ve all had traumatic experiences which colour our judgment.

Lost in the terror of nuclear apocalypse, and maybe understandably so, is the fact that in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s – the period preceding the rise of wind and solar – every cancelled nuclear power plant meant a coal plant got built instead. Through the process of environmental racism, these were probably built – to requote NRDC – “…in communities primarily populated by African Americans, Latines … and low-income workers”.

If they were really lucky / a lot less unlucky, these Rainbow Coalition communities would have “only” suffered from natural gas power plants in their backyards.

In fairness most of the US nuclear industry’s problems seem to have been self-inflicted. Instead of building unit after unit of the same design, allowing successive power plants to be steadily less expensive, every plant was built bespoke. So instead of France’s serial production of nuclear reactors, America got one-of-a-kind artisanal production: the downside of “rugged individualism”.

Still, “we protected the world from nuclear power” rings differently than “we protected the world from nuclear power, and in retrospect it cost the health of a hundred communities poorer than ours”. It’s the Batman line about living long enough to see yourself become the villain. I wrote about Elon Musk being on that arc back in 2017, though it’s now clear he was never a hero, he just paid for good PR.

Wikipedia suggests about 120 nuclear plants were cancelled, so I rounded down above. The carbon dioxide from the hundred-plus coal plants that got built instead, would have been on the order of 100 million tonnes per year of carbon dioxide. Add the fugitive methane emissions from coal production and it’s probably not far from the 160 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (on the Seven Generations timescale) that the natural gas industry causes each year from fugitive methane emissions, as discussed last time.

I’ve had the privilege of working for an environmental non-profit; those were the most ennobling years of my career. Like my colleagues, those long-ago anti-nuclear environmental campaigners were sincere, ethical people – most people in society are – and none of them, fifty years ago or today, would have wanted to sentence disadvantaged communities to a life under a coal plant’s shadow. Theirs was a case of a collective blind spot around “what kind of power plant will get built instead, and where”.

There was no intent to cause suffering on the part of anti-nuclear activists; in fact, they were trying to prevent the risk of even worse suffering. There still remains a moral cost – I’m not smart enough to calculate it, but I’m sure there is one – from the fact that the resulting coal plants didn’t go into the postal codes of anti-nuclear non-profits’ donors or leaders.

Instead, through the horrors of environmental racism (sometimes called fossil fuel racism) it would have been black children, fingernails blue from cyanosis, cradled by their mothers in the middle of asthma attacks; it would have been Latina grandmothers whose emphysema-induced coughing spams robbed them of the chance to play with their nietos in playgrounds; it would have been working class white labourers dropping to one knee, then collapsing completely on the shop floor from particulate pollution-induced heart attacks.

I don’t think the Fred Hampton-led Black Panthers would’ve let that slide. Nor the other members of the Rainbow Coalition. They would have demanded change, and probably an acknowledgement of the [unintentional] damage done.

The Wonder Bread of Blind Spots

Critics of environmental non-profits are quick to point out that many were founded by objectively terrible people. That’s factually correct, but by today’s standards, how many people from past eras weren’t? Our role is to acknowledge, confront and try to learn from / atone for what our predecessors have done. Take it from someone who’s not just Canadian but also part German and part Japanese.

To set the stage for non-profits’ historical blind spot, let me start with a modern one.

A common complaint in climate circles is that the Keeling Curve (showing steadily increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations) was published in 1960 but society largely ignored its warning for decades. That looks terrible in hindsight – but only at first.

In the United States, the Civil Rights Act only passed in 1965, and African American communities have had to continue fighting discrimination since then. Language assistance requirements at polling stations (benefiting Latines, Native Americans and many others) didn’t arrive until the US Voting Rights Act of 1975.

Reproductive rights weren’t secured until Roe vs Wade passed in 1973, and a half century later it has all but been repealed. It wasn’t until 1974 that women in the United States could open a bank account without a male co-signer [the Equal Credit Opportunity Act] and the Equal Rights Act to prohibit workplace sex discrimination, reintroduced in 1971, died in 1982. The gay community had to fight for years in the 1980s to draw attention to and action on the AIDS Epidemic, and 2SLGBTQIA+ people are under renewed threat from bigots. There have been and continue to be many other necessary social struggles.

It took armies of organizers decades just to lift other members of society [closer] to the legal and social dignity offered to economically secure white men. If you time-travelled back and told any of those organizers they should actually be campaigning about climate change instead, you would deserve the incandescent fury they’d direct at you.

Would it have been better for societies to do more, sooner on climate? Yes. Is it 100% understandable that many, maybe most people in prior decades prioritized fights for human dignity first? Also, yes.

By process of elimination, what group in society would have been (and was) most likely to focus on and fund and lead environmental advocacy instead of those other causes? Economically secure white people, and probably mostly men.

That made them susceptible to the asteroid-sized blind spots that plague overly similar groups. The lack of diversity may have been noticed, but as with the gas drilling industry, no one bothered to change things, because that’s just how things had always been done. There was no grand [patriarchal] conspiracy at work, it was just assumed to be an inevitable part of doing [activism], so decade after decade of [environmental non-profits] did things the same way.

White men volunteering for environmental conservation was and remains an objectively good thing. It’s much better than standing on the sidelines! It’s not their fault they weren’t aware of the struggles of more marginalized people in society, and we don’t need a “Hydrogen Ladder” ranking system to score the merits of different types of volunteering and to start judging others who choose “wrongly”. The problem of yesteryears’ non-profits being dominated by white men is that any group of too-similar people becomes susceptible to asteroid-sized blind spots.

It is to non-profits’ credit that they have made authentic and sincere efforts to improve their diversity over the decades. Historically, sadly, to paraphrase Yale’s Wangari Maathai Professor of Environmental Justice Dr. Dorceta Taylor’s searing 2014 paper, The State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations, those efforts mainly consisted of promoting white women into leadership positions. In many ways she’s the “Robert Howarth” of drawing attention to American non-profits’ diversity woes.

Including white women is still important progress. It’s indisputable. Of course, much more still needs to be done. From Dr. Taylor’s research, ethnic minorities were maybe 1/3 of the American population back then, but only 1/6 or 1/8 of surveyed environmental organizations’ staff and leadership.

To channel The Odyssey, the rosy-fingered Dawn will come when all substantial non-profits have the leadership diversity of today’s David Suzuki Foundation. I disagree with DSF on many things – but I’ll applaud when it’s due. Hopefully these sector-wide changes happen sooner rather than later.

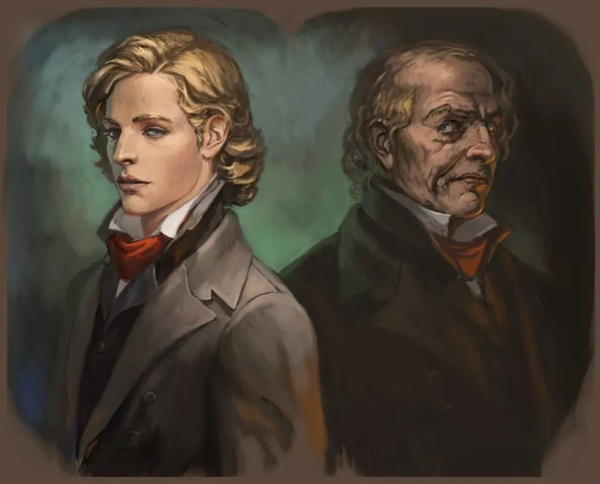

The Sierra Club (of 1972) versus the Black Panthers

In 1972 Sierra Club members were asked whether the organization should include the concerns of the urban poor within their mandate. The majority voted no; Dr. Taylor, writing a guest essay for Sierra Club in 2020, and good on them for inviting her to contribute one, noted it was mainly the old guard who opposed doing so. Maybe in advocacy, as in science, progress sometimes comes one funeral at a time. Happily, by 1976 volunteers had begun conducting outreach in inner cities [see page 21 of Dr. Taylor’s report].

Now we return to the Black Panthers. I can imagine an alternate universe where non-profits’ 1970s anti-nuclear protests were met by Fred Hampton-organized Rainbow Coalition anti-coal/pro-nuclear counter-protests. Environmentalists squaring off against black, brown and lower class white people who fed hungry schoolchildren and by this time even organized free community health clinics, would not have been the “David” in that David vs Goliath narrative. How would they have dealt with pushback from the disadvantaged? How would they have reacted to people from the lower class / underclass “punching up” at them?

I don’t think the Black Panthers could have changed Sierra Club, or Greenpeace, or other non-profits’ positions on nuclear – fears of nuclear Armageddon would probably outweigh anything else – but I bet they would have peeled off part of the anti-nuclear community who (through that shared blind spot) hadn’t thought about the devastation the coal plants that got built instead, would wreak on minorities and the poor.

And again, the American nuclear industry needed no help sinking its ambitions.

Now, Hampton was a dealmaker. Remember, he allied with the Young Patriots, who represented working class whites who emigrated to Chicago from the American South.

In the fiction of wishful thinking, I wonder if he could have convinced anti-nuclear groups to campaign for natural gas plants to get built instead of coal; to advocate for the most stringent available pollution controls; and as proof of solidarity, to get some of those natural gas plants built in or beside wealthier white neighbourhoods. That, and committing to add minority and white working poor representation in their leadership and Boards, and their working committees too. Maybe Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign could’ve started thirty years earlier.

We can’t undo the past, but we can do better in the future. Diversity matters, because shared blind spots and doing things as they’d always been done, decade after decade, can have very big, very negative impacts – even outside the fossil fuel sector.

With a little luck and a lot of hard work we can improve things, document our improvement, and push through outdated stereotypes. Whatever one’s opinions of the Sierra Club, we can all credit that it’s very different, for the better, from where it was in 1972. This will also be true of every environmental non-profit since then.

Calling back to the prior essay, whatever one might think of British Columbia’s natural gas (and by extension LNG) we should all credit that its upstream fugitive emissions are as different from the US average, as Canadian gun violence rates are from American ones.

When pressure is applied to improve practices, through regulators or outcry, organizations tend to improve. And when they do, they no longer deserve to be judged by prior practices or worst-in-class peers.

Forwarded this from a friend? Enjoying energy commentary rooted in empathy? Subscribe here to receive these essays in your email inbox!