Energy R&D: Resilience and Diversity

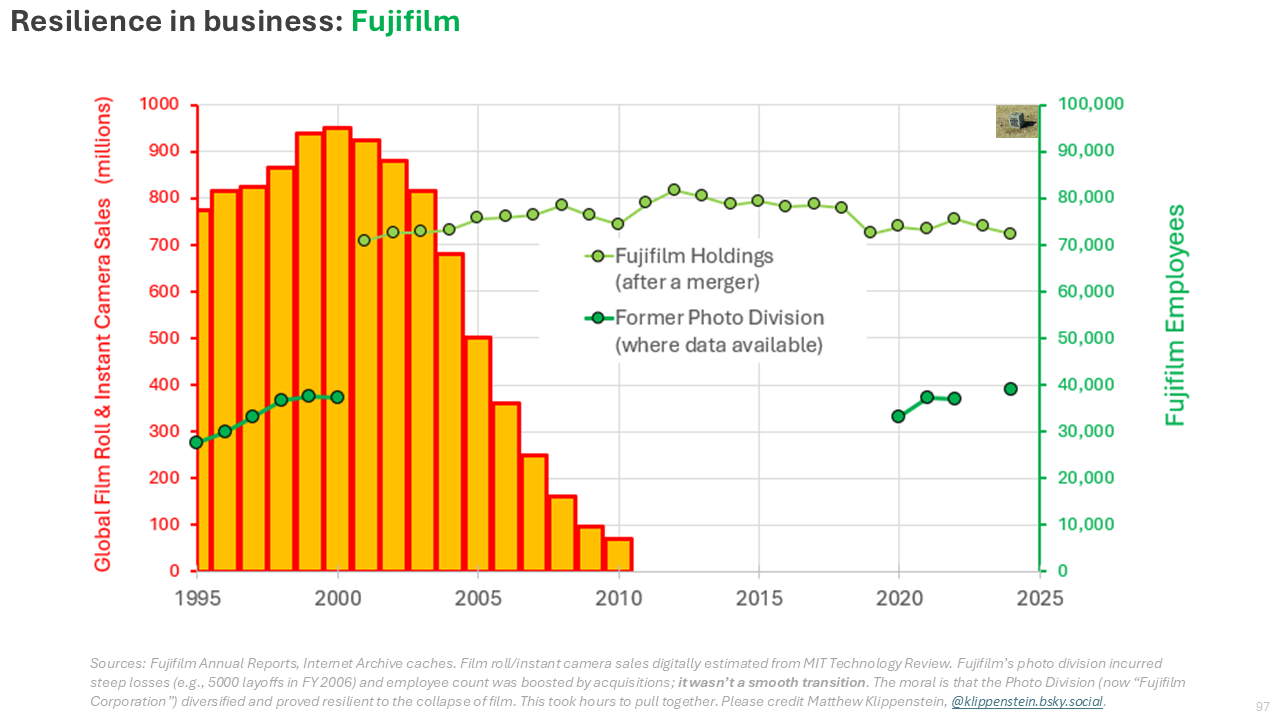

It is a cliché that digital cameras killed Kodak, but it deserves to be a cliché that Fujifilm survived. This example and many others suggest that while efficiency helps us in the short term, resilience carries us to the long term. We should consider this as we think about energy.

[This entry begins a several-part discussion of energy informed by insights from biology to business and civil society – from the Toyota Production System down to photosynthesis, from enshittification to the Race for the South Pole. This is the Executive Summary. Footnotes will be provided in the subsequent instalments. I promise a different way of thinking about energy systems than you've encountered before.]

It is a cliché that digital cameras killed Kodak, but it deserves to be a cliché that Fujifilm survived. Its reinvented film division still has 39,000 employees. Theirs is the lesson that while efficiency helps us in the short term, only resilience carries us to the long term.

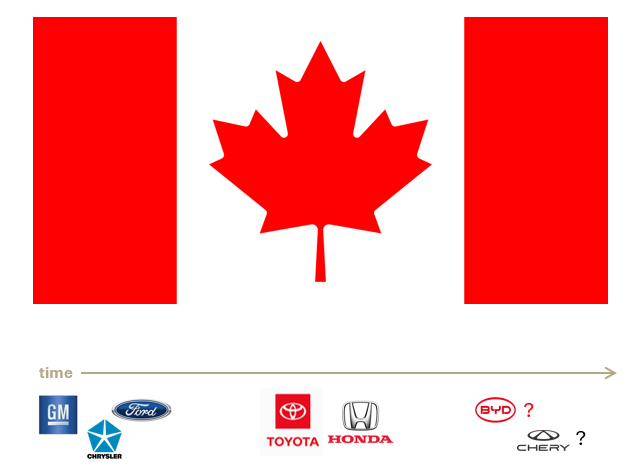

Efficiency has dominated public imagination for the past half century, buoyed by globalization. Recent years however have brought Canada a global pandemic, cascading supply chain crises, escalating natural disasters and a changed world with American tariff risks.

This is a time to remember that from civil society (engineering margins of safety for public infrastructure) to business (Toyota’s strategic stockpiles of key components within its just-in-time production system) and even nature (the astonishing biological success of ant colonies) resilience comes first. While efficiency has value, its blind pursuit leads to enshittification, the American Dialect Society’s 2023 word of the year.

Refocusing on resilience has implications for our energy systems and how we shape them. Many forecasts anticipate an electric grid pairing clean firm power (hydroelectricity, nuclear and other sources) with intermittent renewables (wind, solar) where at times of overproduction, wind and solar energy is curtailed; wasted. This is inefficient but closely parallels photosynthesis, which has endured for 3 billion years. Photosynthesis appears to have evolved not towards efficiency but stability (resilience), and it avoids excess energy adsorption – a near perfect parallel to an electric grid curtailing power generation during periods of excess renewables production.

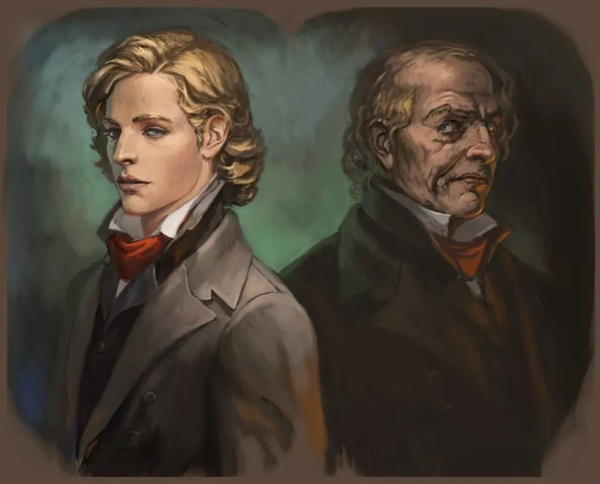

Through the lens of resilience, even with electrification trends, disinvesting in other energy infrastructure – particularly gas – would amount to hubris. Doing so would reduce society’s adaptive capacity. Margins of safety based on the climate and conditions of past decades are probably inadequate for the extremes and disruptions of coming decades. In a warming world of unknown unknowns, redundancies and contingencies will be more important than efficiency. It will have been better to succeed wastefully-in-retrospect like Roald Amundsen at the South Pole, than to streamline our way into a Robert Scott-style disaster: it is better to be prepared than to be efficient.

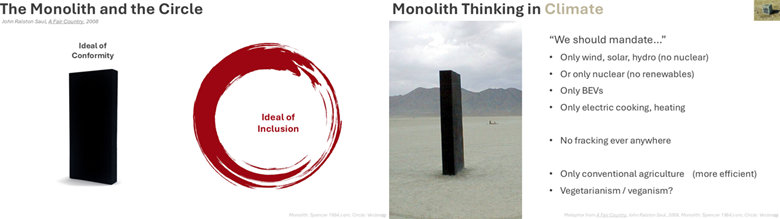

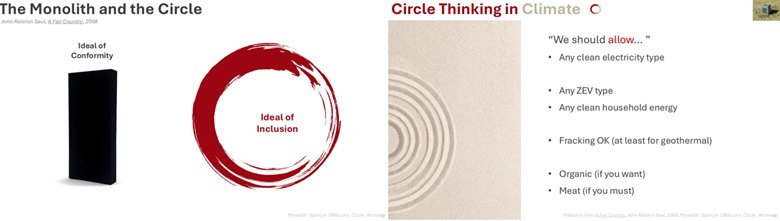

Diversity is not only a matter of energy supply, as above, but a matter of energy consumption as well. We will not build the Canada we want by forcing everyone to be vegan; to live a car-free lifestyle; to only use electric cooking and heating at home. Canadian philosopher John Ralston Saul described this as a Monolith mentality, reaching for utopia by making everyone the same. This mentality has been responsible for many of the worst wrongdoings in Canadian history, from forcing left-handed children to write right-handed; to so-called conversion therapy; to immigration restrictions from non-European countries; to the genocide of forcing supposedly superior Western culture and values on Indigenous children. We will not build the Canada we want on the back of new Monoliths.

Saul commends the inclusive approach – the Circle – which works to integrate differences. Even with encouragement and policy incentives for preferred options, some people will want meat, so we aim to reduce its environmental impact; some people will want cars, so we aim for zero-emission options; some people will want fireplaces and flame stovetops, so we aim to decarbonize the gas supply. Humans have enjoyed fire for 700 thousand years, and we are unlikely to change this preference in the next 0.025 thousand: even the City of Vancouver’s gas ban for new construction allows these exemptions.

Diversity’s priority over efficiency is also found in environmental advocacy, dating to Amory Lovins’ seminal 1977 book Soft Energy Paths, if not earlier. The sixth of Lovins’ 12 theses is that: “the energy problem should be […] how to accomplish social goals elegantly with a minimum of energy and effort, meanwhile taking care to preserve a social fabric that not only tolerates but encourages diverse values and lifestyles”. (Emphasis added.) Lovins was arguing for diversity over efficiency: for the Circle.

No Canadian examination of energy would be complete without considering our large oil and gas sector, and after many premature predictions, peaks in global oil and gas demand do seem near. Some advocates have adopted the Monolith in wanting the sector to stop existing, but a Circle approach of reorienting it for a low emissions world would make jobs more resilient to declining combustion fuel demand.

Here we return to Fujifilm and the 39,000 employees from its former photographic film division. As part of a diversification strategy Fujifilm redirected its collagen expertise into cosmetics and used its library of thousands of film additive candidates to enter the pharmaceuticals sector. These and other measures helped it survive the collapse of photographic film demand.

There are parallels for our oil and gas sector. Advanced fracking technology may have unlocked clean, dispatchable, inexpensive geothermal power – a perfect complement to intermittent wind and solar – and bitumen shows promise as a source of valuable carbon fiber precursors. Paralleling Scott, the cost-efficient choices would be for Canada to assume fossil fuel demand keeps increasing, or that the entire sector willingly winds down smoothly. Mirroring Amundsen, a resilient strategy would fund development of the above contingencies and more.

Efficiency has value and reaps great returns in times of stability, but we are no longer in the comfort of pre-Covid times. Resilience is what gets systems through instability, a lesson we can draw from civil society to business and even nature, to inform energy discussions going forward. Efficiency helps us in the short term, but only resilience carries us to the long term.

[If you found this interesting, please forward to potentially interested friends, and/or consider subscribing to this blog for more. Thank you!]

Supplemental Graphics that would've broken up the flow of the text:

And the excerpt from Lovins' 1977 book: