Dismounting the Hydrogen Ladder: One Error, Two Cases, Rule of Three

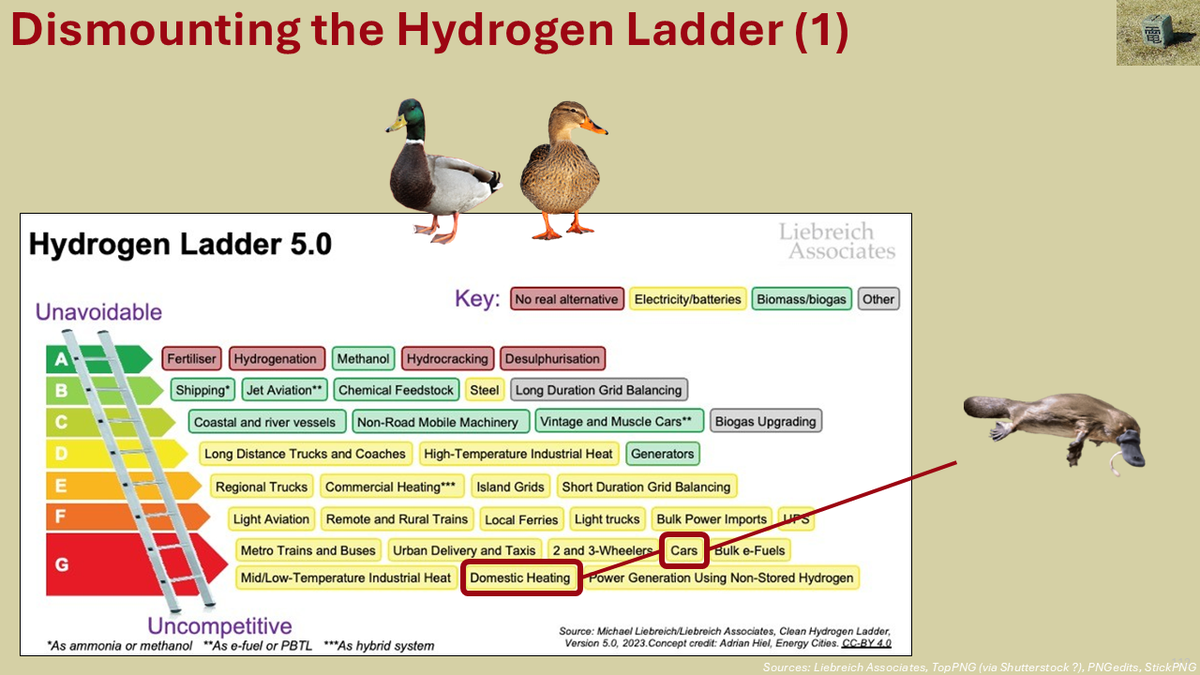

This critique of the Hydrogen Ladder goes to the top of the Hierarchy of Disagreement to refute the central point of arguments against hydrogen in personal transport and households.

[This essay kicks off a three-part critique of a common – but in my mind flawed – rubric called the Hydrogen Ladder, which ranks uses of hydrogen on a scale of “unavoidable” to “uncompetitive”. I’m told some references are obscure, so have added footnotes.

The Energy Resilience & Diversity essay will resume subsequently!]

This is a three-part essay about Michael Liebreich's Hydrogen Ladder, which figures heavily in hydrogen-related energy discussions.

In this part I will go to the top of the Hierarchy of Disagreement and refute the central point of arguments against hydrogen in personal transport and households. These two categories are consumer goods, so cost-competitiveness does not rule. Both are inevitable – “unavoidable” if you prefer – just at different scales. I’ll win over one tranche of readers; the second tranche will respect the arguments; the last tranche will dislike what they reveal.

Now, I worked several years with Ballard Power Systems, and Mr. Liebreich thinks hydrogen in land transport’s day has passed. Mr. Liebreich worked at McKinsey, and I think neoliberalism’s day has passed. So, we’ve both worked on the other’s Betamax.

Of course, where Mr. Liebreich’s accomplishments list is 62 panels long, mine are a tabula rasa. Fortunately, ideas are judged by their merits, not their pedigree.

The one thing I do have that most readers don’t, is experience with both the cost and the consent dimensions of energy. I worked at a non-profit to build support (consent) among stratas (homeowner associations) to install EV chargers in the shared garages of apartments and townhouses on behalf of a government EV infrastructure rebate program in British Columbia. Civil society isn’t Sid Meier’s Civilization™. Our neighbours aren’t NPCs. If we haughtily decide what’s best for them, they’ll hotly oppose us in revenge. Models, spreadsheets and ladders don’t always fully factor that in.

A Dinner with Entrees [1]

First, however, picture Mr. Liebreich with old friends at a white tablecloth restaurant, mid-main course. Someone takes a sip of red wine, checks their Rolex, shares a chuckle and carves themselves another morsel of richly marbled medium rare ribeye beef.

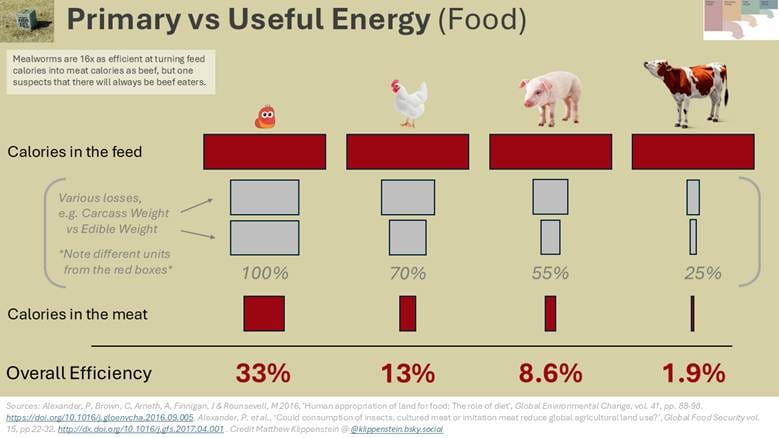

Of course, this scene is four-dimensional madness. Fast food is cheaper; there’s no safe lower limit for alcohol consumption (per W.H.O.);[2] smartphones obsoleted watches; and beef is – to borrow a phrase – a thermodynamic obscenity. It takes 100 calories of feed to make two (2) calories of edible beef; that’s a Sankey Diagram with 98% losses. Mealworms give you 33 calories. If beef was heating fuel, mealworms would be a heat pump with a Coefficient of Performance of 16.[3]

Why wouldn’t Mr. Liebreich and friends be eating at McDonald’s, sipping water, checking time on their smartphones, eating lentil- or larvae-burgers and banking the financial savings in investments yielding 8 percent per year? Because dinner at a restaurant is a consumer experience. For commodity goods lowest cost wins, and winner takes all. But consumer goods are different: lowest cost might take most, but lowest cost never takes all. Consumer choices are based on personal preferences, and personal preferences are diverse.

Many readers will have seen the Model T experience curve, showing how it became cheaper to produce over time. It was surely the lowest-cost vehicle on the market, but its sales stagnated then fell in the mid-1920s. Why? Because cars are consumer goods, and once households could afford more than the very cheapest car available, they bought something different from the very cheapest car available. GM offered “a car for every purse and purpose” and its sales permanently surpassed Ford’s.

If you the reader were gathering with friends, I bet you’d also dine somewhere different from the very cheapest meal available. Dining out is a consumer experience, so cost and efficiency do not rule. McDonald’s may serve more calories than anyone else, but those who can afford to will frequent fancier restaurants. It’s the same way with all consumer purchases. You’re probably reading this on a desktop, laptop, tablet or phone – did you buy the very cheapest product in that category, or something less cost-efficient?

Many consumer goods are “uncompetitive” with alternatives, yet they stubbornly exist. With that in mind let’s turn to our two cases.

Sun Tzu’s Art of Marketing

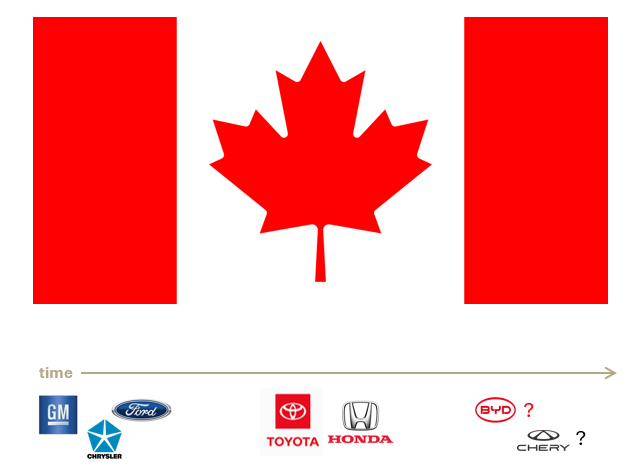

I can’t think of an S-curve technology that has been politically polarized the way EVs are in North America. I don’t think progressives and conservatives traded insults about refrigerators and laundry machines. The Economist opposed public sanitation in the 1850s, but that’s not usually listed on S-curve charts the way electricity is.[4] [5] Maybe because the Harappan civilization built covered sewers before 1900 BCE and that would ruin the x-axis.[6]

In some countries BEVs are associated with the progressive-to-center part of the political spectrum. For some conservatives buying a battery electric vehicle (BEV) would amount to losing face – admitting their opponents were right – making it more likely they stick with fossil fuel combustion.

What does the well-read policy analyst do? They heed Sun Tzu (7.36) and have a zero emission vehicle option for the other side to retreat to. Think of it this way: if Bill McKibben likes BEVs, that makes it less likely for Bjorn Lomborg fans to buy BEVs. If there’s a zero emission option McKibben hates – say, hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) – then his political opponents have a way to go zero emissions while still metaphorically giving him the [Pierre] Trudeau Salute.[7] Would you rather they stick with combustion?

This is the premise of the apocryphal story that the young Warren Buffett did the newspaper routes for both local papers: if someone cancelled their subscription to one paper, he’d sell them a subscription to the other and still benefit. It’s an extension of the “car for every purse and purpose” approach.[8]

The sprinkling of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles poses zero threat to battery-electric dominance, but just as elephants really dislike mice, some battery fans really dislike hydrogen – and with the vigour of 19th century schoolteachers “correcting” left-handedness. We’ll get to that later.

Where [trucking-centric] hydrogen refueling networks with stable pricing develop – and I appreciate that some want to suppress them – quirky people will also want to use it for their cars. Call it the Mallory Rule (“because it’s there”).

The challenges of early, spindly hydrogen networks with shaky uptime and unstable pricing, aren’t a guide for the future – any more than the unreliability of early [non-Tesla] public EV charging networks were. FCEVs won’t be policymakers’ top priority, but hydrogen in passenger transportation is inevitable, at least at a niche level. They’ll be the Filet-o-Fish on the McDonald’s menu of zero emission vehicle automobile options.

Home: the Fire Place

Let’s turn to fire. Humans have used fire for food and warmth for at least 700 thousand years.[9] Idealists want to eliminate that in the next 0.025 thousand. I think they’d have an easier time banning beef.

There are three main domestic uses of fire: home heat, fireplaces and cooking. I think people have emotional attachments with their fireplaces and their cooking: these are consumer experiences. Boilers and furnaces are also consumer goods, but I don’t think people have emotional attachments to them, so these would be much easier to replace; and heat pumps even offer cooling too. Maybe one day they’ll reach a mealworm-like Coefficient of Performance (CoP) of 16.

Would you get everyone to switch to heat pumps? No, consumer preference (and in some cases retrofit costs) would get in the way. That shouldn’t matter for a pluralistic society; advocates can aim for 90, 95, 98 percent and let the rest be. Trying for 100 percent would be chasing purity. How often has chasing purity ended well in the west?

With Canada’s boreal climate my overriding domestic preference is for hybrid heat pumps. It’s far more resilient to keep distributed thermal heating capacity in our winters. Efficiency is an important property for simple machines, but resilience is indisputably the key property for durable complex systems – and our energy systems are dazzlingly complex. If efficiency drove the past half-century of neoliberalism, resilience will drive the coming half-century of [whatever name post-neoliberalism eventually gets].

As for fireplaces and cooking? As consumer experiences they’ll invalidate the widely cited “last grandma” fallacy, which holds that as residential gas use decreases, it will be left to pensioners and the poor to uphold the gas system.

It won’t be the poor. It’ll be the rich. It’s always the rich. Even in a mild-wintered utopia with perfect energy systems resilience there will always be enough price-insensitive rich people wanting fireplaces and fuel stovetops, to maintain the gas network. One-quarter of households in Manhattan own cars, despite spending hundreds of dollars per month on parking fees alone, all of which could sensibly go into investments yielding 8 percent per year.[10] Are those Manhattanites the city’s last grandmas? Of course not. They’re the local gentry.

It’ll be the rich upholding residential gas network costs, and they’ll be able to afford it. In a world of CoP 16 heat pumps, many households would save so much money they’d demand gas connections just for the option of lighting their fireplace now and then to bask in the crackling radiant heat their ancestors enjoyed in the prior 700 millennia – plus whatever new conspicuous consumption marketers come up with. Gas networks won’t have a “last grandma” problem; electrification purists will have a “local gentry” problem.

There will always be households wanting cars, so we created a zero-emission path: ZEVs. There will also always be households wanting fire, so we will offer zero-emission paths: hydrogen or perhaps biomethane. Even if clean hydrogen remains more expensive long term, I think electrification advocates will favour it as the preferred network gas: the relative economics would shift more households to the electric options those advocates prefer.

The continued use of fire in some homes is inevitable. The policy choice is whether to support hydrogen blending and other early trials that will make it easier to move off fossil carbon-containing fuel sooner – or to unskilfully cling to the hope that after 700 thousand years everyone, even price-insensitive patricians, will neither want fireplaces nor flame stovetops, nor mobilize in perfervid opposition to mandatory electrification. Again, I think it’d be easier to ban beef.

The Rule of Three

While most energy professionals arch a puzzled eyebrow at hydrogen, a few really slam it for personal transport and heating. You’ve probably read them, seen them, heard them.

Maybe you can imagine their tone, their intonation, their exasperated hand-gestures. To make it extra vivid, round out the details: the clothes they’re wearing; their home office or virtual background; their favourite turns of phrase. There they are, righteously ranting that compared to electricity, hydrogen is innately inferior; its supporters are stubbornly resisting progress; they’re depraved!

Hold that thought.

Roll it around your hippocampus.

Crystallize the image, as if you were going to paint its portrait.

Seeing Red (page 6) notes how, in the Canadian press as in Canadian culture, Indigenous Canadians have historically been stereotyped as having three characteristics – depravity, innate inferiority, and a stubborn resistance to progress. Here’s the full sentence: “In general it avers that Aboriginals, when compared to white Canadians, exemplify three essentialized sets of characteristics – depravity, innate inferiority, and a stubborn resistance to progress”.

How about that?

Isn’t that interesting?

I think it’s interesting.

But we can go further. If you have Christian European ancestors like me, let’s go from 1925 Canada to 1425 Europe, a century before my ancestors went from the scapegoaters to scapegoats themselves. How do you think Christians back then described Jews and Judaism? We know the influencers of the day wrote hateful, vile, evil rants about their targets’ depravity and stubborn resistance to progress – and how their choice of faith was innately inferior. We have their writings – in ink as black as their hearts of darkness.

Read them yourself.

Time really is a flat circle.

In school I learned about the Law of Conservation of Mass and the Law of Conservation of Energy, but this is a Law of Conservation of Contempt.

I bet that no matter how tolerant a society becomes, a fixed percentage of people will still have a psychological need for outgroups to target with contempt. When they decide on one, they will condemn it based on that Rule of Three: depravity, innate inferiority, and a stubborn resistance to progress. Contempt is one of the seven basic emotions, so we’ll never eliminate it from society, but our choice as individuals is whether to decline that torch or carry it: to stand on the shoulders of giants or shout in the shadows of [people who are obstinately or intolerantly devoted to their own opinions and prejudices].

It's statistically inevitable that some people who denounce racism, sexism, 2SLGBTQIA+ discrimination and other evils, will want a new scapegoat, and hydrogen turns the crank for a few. While their peers shrug about different strokes for different folks, they’ll pour their frustrations and project their failings onto it, as all scapegoaters do. With my professional, national, and epi/genetic backgrounds, it was also statistically inevitable that I’d defend it.

Is hydrogen arguably suboptimal for many things? Sure. But all our consumer preferences will be arguably suboptimal in some other person’s eyes. Anyone at half your household income level would reclassify a lot of your must-haves into don’t-needs – and you would be outraged if they tried to take those treats away.

I would love to see a speaker give their contempt-venting two minutes’ hate on hydrogen in personal transport and households, then turn to a Rabbi or [Indigenous] Elder in the audience and insist that in 1425 or 1925, with the biases and bigotries of the day, the speaker would have treated their outgroups with respect. [Jennifer Lawrence “sure, buddy” meme.]

For me that’s the test. You do you, of course; I’m not going to police your preferences. It’s easy for me to denounce my genetic ancestors and national predecessors from here in 2025, but that doesn’t prove I’d’ve acted differently back then; prevailing attitudes have, thankfully, improved. So, what would have given me the best chance of doing the right thing centuries ago, despite the biases and bigotries of those eras? Rejecting contempt.

If you’ve only ever worked on the cost side of technology, this all might sound like biomethane feedstock to you; why should you care? You should care because this matters absolutely when it comes to building consent – which we will have to do a lot of, to transition to a renewables-dominant world. You don’t build consent in a strata (homeowners association) or a community by treating differently minded people with contempt. If you do that, you’ll lose their support – and the support of a dozen onlookers who conclude you’ll treat them with contempt on the day they disagree with you. You’d galvanize opposition, all for the brief smug high of feeling superior.

You build consent by being humble and respectful, and by doing your sincere best to accommodate every concern and preference – even if it costs money, even if it costs time, even if it costs efficiency. Because that’s how you build trust. And in our generational task of lifting living standards while sinking emissions, “more trust” is more valuable than “mere efficiency”.

The Standing-on-one-foot Summary

Is electrification the future? Yes, but it can come in two ways: aiming for purity or accepting diversity. Now I’m an atheist, and atheism is clearly the future. But the Republic of Klippensteinia would welcome and embrace religious people and their peculiar preferences; we’d hew to Ashoka, not Wuzong.[11][12] I’m not sure about Richarddawkinsstan – and a lot of enthusiasts seem to want a Richarddawkinsstan of electrification.[13]

This recalls when westerners eliminated wolves from Yellowstone National Park under the logic “bison good, wolf bad”, over the baffled disbelief of Native Americans who saw nature as the equilibrium it is: huge herds of bison and the occasional wolf.[14] There will be a similar equilibrium with consumer goods: mostly electricity for personal vehicles and household use, with some fuel (hydrogen) rounding those out. The hydrogen is no more “bad” than the wolves were; it completes the healthier ecosystem.

The standing-on-one-foot summary – and that is the greatest framing I have ever found for any faith teaching I’ve had the privilege to learn – is that [when it comes to consumer preferences in the energy transition] we respect others’ frivolities so that they respect ours. Those might be odd, “illogical”, and annoying, but in a pluralistic society we choose inclusion over efficiency, inconvenience over contempt. We trade time, cost and efficiency for trust, and we do this deliberately.

Back to the Hydrogen Ladder, being consumer goods, the frivolity of hydrogen in passenger vehicles is inevitable (in a niche way) as is hydrogen-or-biomethane in households (in an extensive way). To group them with commodity goods is to put a platypus in a duck exhibit; to try to suppress them is to fight human diversity. Consumer goods need to be moved, preferably to their own category, because relative cost does not rule consumer markets. Let he who has traded beef for mealworms cast the first stone.

[1] Yes, this is a pun.

[2] https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/04-01-2023-no-level-of-alcohol-consumption-is-safe-for-our-health

[3] Heat pumps today typically have a Coefficient of Performance (CoP) of 3 or greater. This means they can move 3 units of energy into/out of a house (whether for heating or cooling) for each 1 unit of electrical energy consumed. They are marvellously efficient devices. Refrigerators operate in the same manner, and can also remove 3 (or more) units of heat from inside the fridge to the rest of the kitchen, for each 1 unit of electrical energy consumed.

[4] https://archive.thinkprogress.org/krugman-the-economist-opposed-attempts-to-improve-public-sanitation-in-the-19th-century-b8602f8b69ff/

[5] http://steveboese.squarespace.com/journal/2015/12/16/chart-of-the-day-the-technology-adoption-curve.html

[6] https://www.harappa.com/lothal/14.html

[7] https://nationalpost.com/news/politics/a-b-c-museum-says-its-preserved-the-railcar-from-which-pierre-trudeau-gave-the-finger-to-protesters

[8] Sadly, this seems to merely be apocryphal. It may be a conflation of his delivering up to five separate newspapers in his youth and simultaneously selling magazine subscriptions to his customers.

[9] https://www.theguardian.com/science/2012/apr/02/scientists-clue-human-evolution-question

[10] https://www.hunterurban.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Car-Light-NYC-Infographics-May-2024.pdf

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashoka%27s_policy_of_Dhamma#Edicts

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huichang_persecution_of_Buddhism

[13] Richard Dawkins being a prominent atheist fiercely critical of religion

[14] https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/wolf-management.htm