Dismounting the Hydrogen Ladder 3: A Farewell to Army Knives

The particulars of our places punish the general tool, whether a Swiss Army Knife or the Hydrogen Ladder. We use tools fit-for-purpose, instead. So a Hydrogen Star is proposed.

In Part 1, I argued that because consumer goods differ from commodity goods, hydrogen in personal transport and domestic use is inevitable (at different scales). I also proposed a Law of Conservation of Contempt.

For readers who want everyone to live “A Certain Way”, I offer this quote from RMI founder Amory Lovins’ 1977 Soft Energy Paths: the energy problem should be “…how to accomplish social goals elegantly with a minimum of energy and effort, meanwhile taking care to preserve a social fabric that not only tolerates but encourages diverse values and lifestyles.” (My emphasis.) Maybe if RMI gets enough emails, Lovins will recant his commitment to diversity and inclusion. It worked on US universities, I hear.

[DO NOT DO THIS. I am criticizing intolerant ideologues and the cowering administrators they bullied. Does great power no longer come with great responsibility?]

In Part 2, I argued there are flaws in rubric overreliance. Rubrics can sometimes mislead, so we have to do our homework (genchi gembutsu) in every situation. On paper and by first principles you’d think the US military would’ve won in Vietnam – but if you learned that the Kingdom of Dai Viet went 2-1 against the Mongol Empire, losing only the first campaign, you’d’ve been prepared for the outcome. Sometimes our homework surprises us.

From Industrial Policy …

In Part 3, I want to propose looking at hydrogen through the lens of coordination; “no man is an island”, as the saying goes. Everything we do and build in life happens in a web of connections and constraints, and is shaped by coordination and conflict.

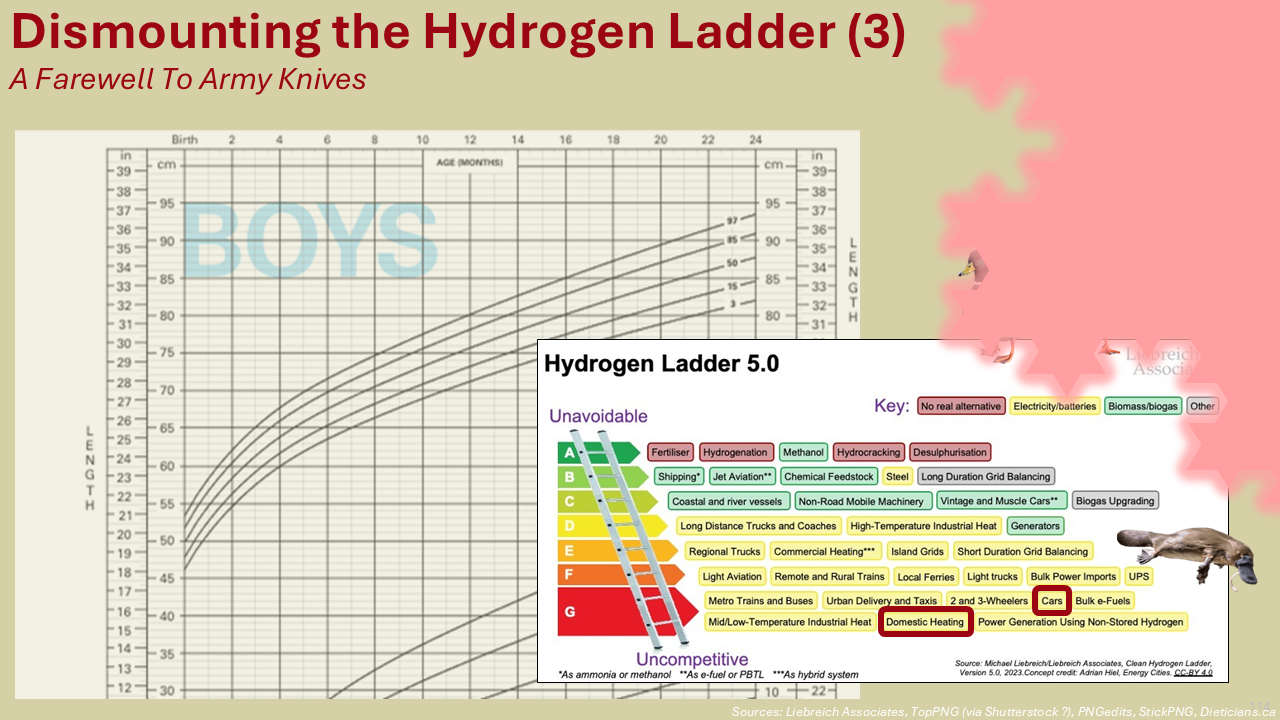

No deployment is an island, either, but the Hydrogen Ladder’s entries are separate, atomized, isolated, on their own. Every individual (deployment) for themself. Like the Margaret Thatcher saying that there is no such thing as society. Neoliberalism.

I’m mostly mild – I won’t waste my life being angry – but to reverently quote the Bhagavad Gita, my hostility to neoliberalism burns with “the radiance of a thousand suns”. Maybe it was inevitable; our next-door neighbours in the housing co-op growing up were refugees whose relatives were “disappeared” in the neoliberal laboratory of Chile. Maybe with enough Buddhism-channeling mindfulness practice (Part 2) I could turn my feelings down to the low glow of dying embers. Readers’ opinions about neoliberalism can and should vary. Like Lovins, I support diverse values and lifestyles. I’m a non-judgemental leftist. My conservative friends say I’m a minority. Maybe that’s why they keep peeling working class voters away from us.

I like neoliberalism’s nemesis, industrial policy, and not just because it’s key to helping cheap, clean hydrogen scale. When we stabilize global mean surface temperatures, it’ll be on the back of the coordinated action of Chinese industrial policy: a Cambrian explosion of cheap solar, cheap batteries, cheap battery electric vehicles, and perhaps another technology or two.

These industries have scaled frenetically, and someone’s probably made the argument that the Chinese government is mired in a financial boondoggle. Maybe. Even if so, it would be a small price to pay to reduce China’s reliance on seaborne fossil fuel imports when Britannia America rules the waves.

Non-neoliberal economist Karl Marx might highlight that China now controls the means of production (well, the world’s cheapest production) of strategic technologies, giving it leverage over the Global North. Happily, unlike tax cuts for the rich, the climate benefits of this ever-cheaper cleantech actually will “trickle down” to the rest of us. Mr. Liebreich and the NEF/BNEF team deserve much credit for foreseeing the fruits of China’s industrial policy before almost anyone else. I unreservedly tip my toque to them for that.

I don’t know if we’ll call this new era Xi-ism (after the Chinese President), Gang-ism (after the grandfather of Chinese EV policy) or Mazzucato-ism (after the most prominent Western industrial policy proponent), but I’ll be happy to “Just Transition” neoliberalism into the nursing home of intellectual speculations, like the outdated “blueberry muffin” model of the atom, or the “phlogiston theory” of combustion.[1]

We’ll get to hydrogen after I acknowledge that industrial policy can go wrong. Absolutely. And expensively. But would you dismiss democracy based on America’s current tribulations – or the election of a socialist in 1970s Chile? We have a library of examples where industrial policy has succeeded, so it’s more a matter of doing it properly. To paraphrase a chapter in economist Ha-Joon Chang’s Bad Samaritans, industrial policy’s critics have a Monty Python problem:

Now let’s move to hydrogen.

…To Hydrogen Hub/bub

I’m sure there will be successful one-off hydrogen deployments in the energy ecosystem but – as with the broad consensus – much/most activity will develop around coordinated use: hydrogen hubs. Industrial policy.

This would parallel biology. Only 2 percent of insect species are eusocial – living together in colonies, like ants or bees – but those 2 percent are about 80 percent of global bug biomass.[2] Many insects in earth’s ecosystem eke it out with “rugged individualism”, but the ones who coordinate together, dominate together.[3]

We should still let non-target industries organically grow to their fullest potential, of course. Japan focused on steel, machine industries, autos and electronics, not comic books -- but manga comics have grown so much they now outsell superhero comics even in America.[4] There’s an iconic business school paper to be written about how cheaper black-and-white manga disrupted western superhero colour comics from below, while simultaneously outflanking them with different genres (like GM’s early purse/purpose strategy from Part 1). If you eventually write that paper, please reach out.

Once we think in terms of coordinated action, I believe there is value in representing scale-of-use as well, to show how different deployments compare to each other.

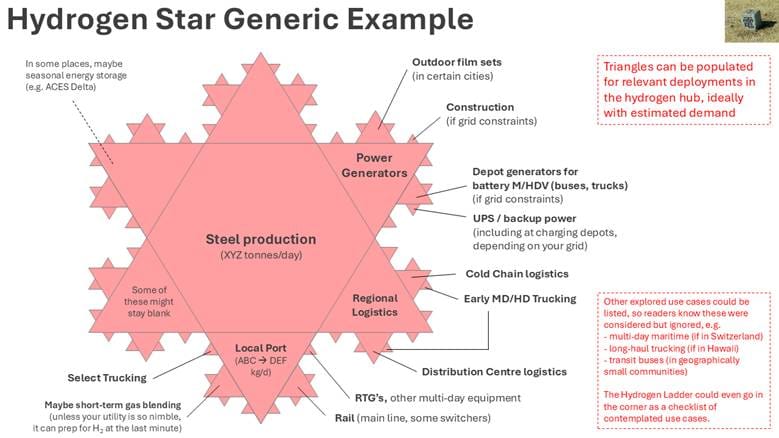

I’ve seen many detailed depictions of hydrogen hubs by talented graphic designers, and think there is room for a radically simplified visual: the hydrogen hub equivalent of Picasso’s lithograph The Bull. Something informed by the scales of different use cases, which the Hydrogen Ladder also lacks.

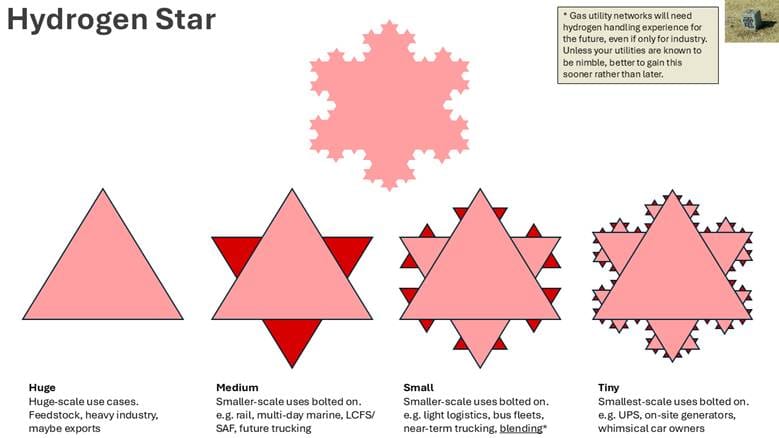

So, I want to offer a Hydrogen Star – a fractal shape based on successive triangles. It starts with a big triangle, then smaller triangles are placed along the middle 1/3 of each exterior line, and so on. I’ve blandly labelled the sizes as Huge, Medium, Small and Tiny.

Annotating the Hydrogen Star

The Hydrogen Star offers a way to visualize the central importance huge hydrogen use cases – mostly industrial feedstock or high heat, one imagines – with successively smaller use cases bolted on. A harmless example might be how small barnacles affix onto big whales. A harmful example might be how a fan ecosystem affixed to Elon Musk, explaining away a Soviet parade’s worth of red flags over the years.

The Hydrogen Ladder might be complementary as a prioritization list, but it remains necessary to do the homework for each specific situation (genchi gembutsu from Part 2). The Hydrogen Star wouldn’t diminish the challenge of getting major hydrogen production projects to FID (Final Investment Decision) but knowing scale-of-use would help visualize easier versus harder paths forward. The Hydrogen Star makes the knowledge more actionable.

For example, vintage and muscle cars rate a “C” on the Hydrogen Ladder – fairly high – meaning they’re less likely to be displaced by other alternatives. But there aren’t many vintage cars, and they’re not generally used for daily driving, so they would consume tiny amounts of hydrogen. Their consumption would be minuscule – the hydrogen equivalent of, I don’t know, an artisanal cheesemaker. Supplying them on their own would be a very high-cost affair. Not that the hydrogen price would be a likely showstopper: these are rarely used consumer goods owned by enthusiasts. The bigger question is whether those enthusiasts will be scorned the way non-vintage hydrogen car enthusiasts are.

Public transit buses get the lowest rating of “G”, but if you do your genchi gembutsu and batteries won’t do for all routes, ten hydrogen buses might together consume 200 kg per day. The low ranked bus use case contributes more hydrogen demand than higher ranked vintage/muscle cars, making buses more relevant for an industrial policy around hydrogen. Have some [hydrogen/battery] bus deployments struggled? Yes. Is that an argument to abandon [hydrogen/battery] buses? There’s no shortage of nuclear or fossil fuel purists celebrating every renewable energy project setback, such as how three-quarters of American wind and solar projects requesting transmission interconnection, never get built.[5] True. So? Neither do two-thirds of gas power plant interconnection requests.

[For sure, batteries will improve over time, gradually favouring battery buses. There remains much upside for hydrogen buses. Urban bike infrastructure is improving over time, steadily favouring cycling, but I foresee much upside for more expensive, less efficient battery electric vehicles in cities.]

Trying to ration hydrogen only for higher-ranked use cases would lock-in more fossil fuel combustion longer, while reanimating the corpse of ideological planning, one of my and neoliberalism’s few common foes. Central planning is everywhere – Apple, Walmart, and every public and private organization of size relies on it – and is powerful when it adapts to data, as Toyota’s battery electric vehicle strategy eventually did. Even the Mongol Empire changed tactics when its invincible cavalry archers proved to be actually very vincible [defeatable] once the Vietnamese forced the fighting into dense forests. And yet, decades of data later, the push for tax cuts for the rich continues…

A Farewell to Arms Army Knives

In the perfect vacuum of neoliberalism, unfettered by scale of use and real-world factors, where the long-term tomorrow’s technology and infrastructure exist today, the Hydrogen Ladder is probably pretty good.

[Thanks to Chinese industrial policy, it might be the medium-term tomorrow’s technology. But depending on the reader’s utility, NIMBYs (including working class people we’ve alienated) and the personal vendettas of authoritarian populist politicians (supported by working class people we’ve alienated) – it might be the very long-term tomorrow’s infrastructure. With energy, cost is the easy dimension; consent is the difficult one.]

Unfortunately, we don’t live in a model world. We live in the present world, and the particulars of our places punish generalization.

That’s why we put away a Swiss Army Knife the moment we have a more specific, fit-for-purpose tool.

That’s also why we’d put away the Hydrogen Ladder the moment we’re dealing with a specific site/region/hub. We’d use a tool fit for that site/region/hub’s specific needs – one that can be populated accordingly.

I’ve proposed a Hydrogen Star to fill this need. I’ll happily defer to others’ tools as they prove better. Even if it turns out they’re neoliberals. Because at the end of the day, when our advocacy is done, with the rarest exceptions, it’s not our place to police others’ lifestyles and values.

[1] The former is also known as the plum pudding model of the atom: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plum_pudding_model. Phlogiston theory proposed that a special compound – “phlogiston” – caused combustion: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phlogiston_theory.

[2] Ref. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK242457/; estimates of 75 percent are also common, but would subtly imply more accurate knowledge (“not 74, not 76”) than we have.

[3] A reference to the brain science expression that “neurons which fire together, wire together”.

[4] https://www.cbr.com/japanese-manga-vs-american-comics-why-more-popular/

[5] Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories, Queued Up: 2024 Edition, page 28