Dismounting the Hydrogen Ladder 2: Rubric Overreliance

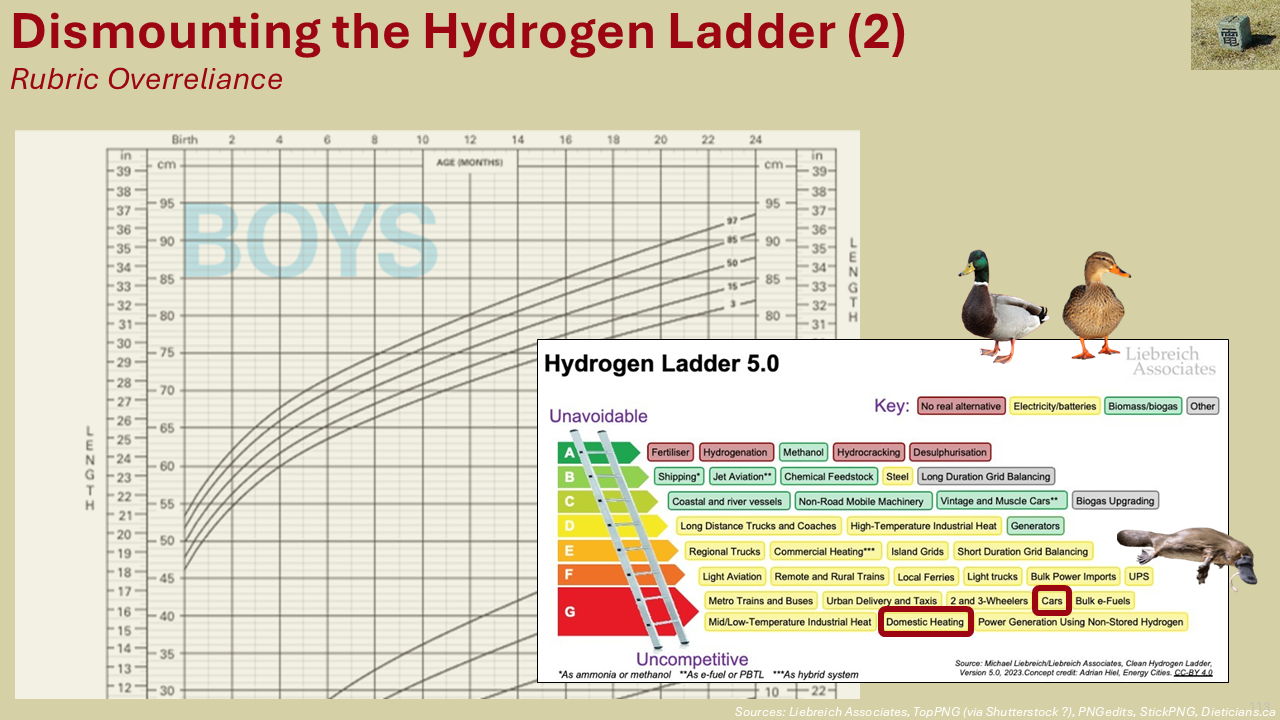

Scoring rubrics can be helpful, but from 17th century farming to pondering hydrogen uses today, they can steer us in the wrong direction.

[This is Part 2 of a three-part critique of a common – but in my mind flawed – rubric called the Hydrogen Ladder, developed by Michael Liebreich, which ranks uses of hydrogen on a scale of “unavoidable” to “uncompetitive”. Part 1 is here.

The Energy Resilience & Diversity essay will resume subsequently!]

I use social media lightly, but even so, have learned much from Mr. Liebreich’s posts. Three big memories stand out: he cheered on Brexit in 2016, declared mid-Covid that 2019 would mark the all-time peak of oil consumption,[1] and caught flak for buying a combustion SUV a few years back. Everyone makes mistakes, I’ve certainly made mine, so I want to focus on the combustion SUV, because that wasn’t one.

Here’s my take.

Who cares?

Does Liebreich go around pestering transit agencies that choose hydrogen buses, nagging gas utilities exploring hydrogen, mocking road and rail freight piloting it?

Then why should we behave any differently?

Who’s the best positioned to know Liebreich’s needs? Liebreich and family. No one else. To think differently is to infantilize his judgment. It’s profoundly insulting to him.

At best you’d politely approach him and say, “on a scale of Nero to Optimus Trajan, combustion SUVs are a Domitian, right? I must be missing something, though, so please enlighten me.”[2] You’d accept that your preferences are not his priority; that you’re neither the protagonist of his story, nor the feather of Ma’at judging him.[3]

All of which applies to the transit agencies, gas utilities and road and rail freight too. It’s possible they had blind spots, sure. But it’s far more probable that an outsider – especially an outsider with preconceptions – has many more, and bigger ones too.

We’ll all be citing management principles from ascendant Chinese electric car titan BYD soon, but for now we have Toyota, and the Toyota Production System’s problem-solving practice of “genchi gembutsu” applies perfectly: to solve a problem, you have to go to it and see it for yourself.[4] This is because second-hand information and assumptions can, and often will, lead you astray. You want to be unfettered by preconceptions, because being besotted by a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. You may know the latter as the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Where Zen would have us approach matters with Beginner’s Mind,[5] I see people grabbing the hydrogen ladder and pole vaulting into Dunning-Kruger mind. There’s nothing wrong with a scoring rubric – Sir Mix-a-Lot had one, Nicki Minaj too – but a rubric can distract you from what works best in real life. The rubric is not the reality; the map is not the territory; and the finger pointing at the moon, is not the moon.[6]

I will illustrate the problems of rubric overreliance with a personal example before moving to more profound ones.

Charting Healthy Growth

Like all parents we fretted about our firstborn, and according to baby height and weight charts he wasn’t growing properly. So, we went to our doctor. She, an East Asian woman, looked at our baby, looked at us, looked back at the baby, and said:

“Your baby is what, three-quarters East Asian? This chart” – she held it up – “was mostly based on Caucasian babies. East Asian babies develop more slowly, so it doesn’t apply to him. Let’s focus on Baby instead; is he feeding well, is he filling his diaper, is he gaining weight steadily?”

The doctor didn’t say, “this is stupid, you’re doing it wrong, force-feed him if you need to, make him fit this rubric.”

[Roughly contemporary Canadian media article about this very real phenomenon, here.]

The rubric – the growth chart of how babies “should” grow – had gotten in the way of our assessing our baby’s real-life health. It was made diligently and conscientiously by many smart people, and it applied to a lot of babies – but not to babies of all ethnicities. The growth chart got in the way of our direct observation (genchi gembutsu) of our infant son to gauge his health. It had become the distorting mirror of the Christian idiom about how we see the world as if looking through a glass darkly. [Mirror quality in antiquity was poor; the ancients lacked modern tools, among them the Toyota Production System.]

The hydrogen ladder is like that baby growth chart. It has value, is the product of many smart and conscientious people, and is easy to apply – but its intrinsic assumptions can’t encompass all situations, making it easy to misapply too. Better to evaluate every hydrogen deployment on its unique situational merits, than a priori pre-select an answer.

A “hockey scouting ladder” would have a priori rated the young Wayne Gretzky poorly: on paper a thin, scrawny, one-dimensional player should not belong in the NHL. But seeing his play or point totals (genchi gembutsu) would have underscored that hockey wisdom is more rule-of-thumb than rule-of-law. Mr. Liebreich demonstrates this himself: subtle but widely entrenched social biases mean that the “promotion-to-management ladder” favours tall, thin, white men from elite backgrounds with a full head of hair. Liebreich achieved great success because enough people looked past second-hand assumptions (the ladder) and directly at his track record (genchi gembutsu), which I understand was formidable.

Now I will move from the personal examples to the profound ones.

Saul’s Parable, Suzuki’s Masterstroke

To paraphrase Canadian philosopher John Ralston Saul[7] the quintessential Canadian parable goes something like this: “European explorers were met by First Peoples in canoes and mocked that the locals didn’t have the wheel. Within weeks the Europeans were paddling canoes.”

This is a jab at white western males’ expense. It still encapsulates a deeply rooted truth: Europeans arrived in the Americas with a little pride and a lot of prejudice towards Indigenous practices.

Recent research (Mt. Pleasant, 2011) has shown that in the 1600s the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) had agricultural yields 3x as high as contemporary Europeans. That’s not a misprint; the so-called primitive First Nations/Native Americans grew 3x as many calories per acre as so-called civilized European farmers did. This was mainly due to higher calorie crops and a clever farming technique. Which, to be fair, western farmers eventually adopted. Based on the ads I saw on CNN growing up, the S-curve of American no-till farming started around 1991.

Why the delay?

Europeans sailed in with Dunning-Kruger Mind and replicated their European farming practices in North America. They were blinded by a rubric whose dictums included, “first thou shalt plow” and “we’re smarter than them”. Plowing may still have been the best choice for European soils – but it wasn’t the best choice for the soil in that part of North America.

A Zen master would’ve told the Europeans to go in with Beginner’s Mind, studied first-hand (genchi gembutsu) how Native Americans farmed the lands, and considered whether these exotic techniques might have merit in this place the locals called Turtle Island.

Nor is this theoretical: 19th century Buddhist teachers such as Daisetsu Suzuki noticed the ascendancy of scientific thinking in the west (genchi gembutsu). So instead of introducing Buddhism by analogy to Christianity, as was the typical practice, they framed it as a pre-modern, empirical “science of the mind” which welcomed – instead of resisting – the scientific revolution. To this day Buddhist monastics enjoy a cozy (too cozy?) relationship with neuroscientists who study the brain, and the mindfulness movement has embedded certain Buddhist (and shared Hindu) practices across the secular world.[8] I think the computer game Civilization™ calls this, Cultural Victory.

None of this would have happened if Suzuki had journeyed to the west[9] with Dunning-Kruger mind, cross-referencing Christianity and opposing scientific naturalism and everything else that could undermine Buddhist religious authority.

I hope this illustrates the difference between the people who pestered Mr. Liebreich about his SUV, and the ones who figured there was a logic they couldn’t see. As with people somehow angry if, say, a public transit agency, having done genchi gembutsu on their specific needs, bought some hydrogen buses in defiance of a second-hand, battery-only, Dunning-Kruger rubric.

When You Assume

As with all rubrics, the hydrogen ladder has trustable value only within the borders of its implicit assumptions – like that Caucasian baby-specific growth chart, or the tilling-based farming of 17th century Europe. Within those borders, the Gestalt of expertise probably works well. It’s always open to Beginner’s Mind cross-examination but probably has subtle merits an outsider won’t appreciate.

Unfortunately, if you don’t notice when you’ve crossed those borders, you’ll trip over wrong assumptions into Dunning-Kruger Mind. Like how there were quantifiable skill differences between the young Wayne Gretzky/Michael Liebreich and the fit-for-stereotype peers they competed against.

The hydrogen ladder ranks hydrogen’s relative competitiveness in various use cases in the abstract. The problem is that you can “Sykes-Picot Agreement” your energy recommendations if you ignore the realities on the ground.[10] Not every use case is a commodity good (see Part 1). Local conditions/constraints will influence the ease of electric energy service alternatives in any given region, so deployment might not follow rank. Relative pricing between hydrogen and electric options may differ from region to region. There are surely other circumstances too.

To draw one last time from the Buddhist well, there’s a difference between rote learning (e.g. a rubric) and true wisdom (knowing how to skilfully apply it). The hydrogen ladder seems suitable as an after-the-fact, probabilistic cross-check – “wow, for this use case we’re the left-handed minority in a mostly right-handed world” – but would be harmful if misused as a prescriptive tool – “you’re doing it wrong, make it fit this rubric”. There are more variables in heaven and earth than are reckoned in its hierarchy, as was the case with that Roman Emperor ranking of combustion SUVs.

I will propose an alternate perspective on hydrogen to conclude this series.

[And then, as they say, I'll return to regular programming. 😊]

[1] It didn’t.

[2] Until the 20th century Domitian was thought to have been one of the worst Emperors. He’s now considered one of the better ones, often ranked just below the very top tier. Domitian hated the Senate so much he instituted promotion-by-merit instead of promotion-by-bloodline. This laid the groundwork for the Golden Age of Rome – and for the Senate and upper-class writers to condemn his name and reputation after death. Mr. Liebreich’s combustion SUV is probably the same way: criticized at the time but proven right in hindsight.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maat#Weighing_of_the_Heart

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genchi_Genbutsu

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shoshin

[6] This too is a Zen reference: https://www.upaya.org/2018/10/palma-finger-points-moon/

[7] I’m pretty sure this was in A Fair Country

[8] Evan Thompson’s Why I Am Not a Buddhist is a worthy read; a shorter criticism of “Buddhist modernism” can be found in this interview. https://www.lionsroar.com/evan-thompson-not-buddhist

[9] A pun on the classical Chinese novel “Journey to the West”, which influenced, among other things, the Dragonball comic / cartoon / merchandising empire.

[10] The Sykes-Picot Agreement is generally “credited” with creating a lot of the violence in the Middle East: the two European diplomats drew new national borders on a map of Ottoman Empire territory according to their first principles (“to the winners go the spoils”) instead of considering local factors. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sykes%E2%80%93Picot_Agreement#Modern_politics