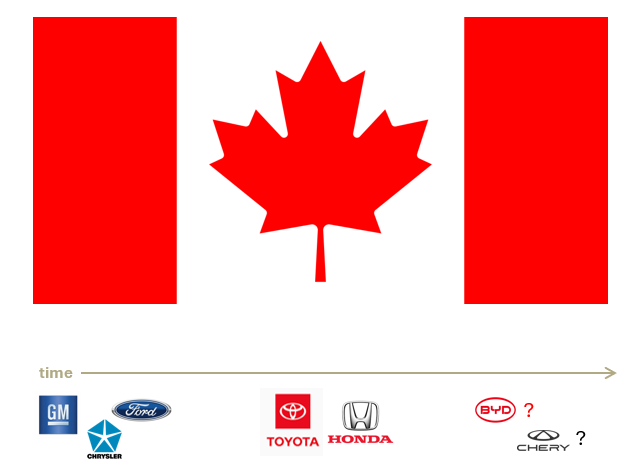

Canadian autos: Big Three to Japan Two … and a Chinese One?

Toyota and Honda first set up in Canada in the 1980s, so in the span of 40 years Japanese carmakers went from an existential threat to the Canadian auto industry, to our biggest producers ... “If you can’t beat ’em, make ‘em join you”.

[Happy New Year! Before I forget, Latitude Media ended their 2025 coverage with my commentary! It’s about survival rates for all manner of energy infrastructure project proposals: surprisingly low.]

Forty years ago, the Canadian auto sector (dominated by the Big Three: GM, Ford, Chrysler[1]) were alarmed by imports from the juggernaut of Japanese carmakers. An arrangement was made: access for factories (“localization”).

Today the Canadian auto sector (dominated by the Japan Two: Toyota, Honda) are alarmed by imports from the juggernaut of Chinese carmakers. An arrangement has been made: access for factories.

Maybe forty years from now the Canadian auto sector (dominated by Chinese firms?) will be alarmed by imports from the juggernaut of Nigerian (?) carmakers. And an arrangement will be made … 😊

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

I’m hardly the first, fifth, or even fiftieth to share thoughts about the recent Canada/China agreement to allow some China-manufactured EVs into Canada. When you can’t win on speed, you try to win on depth, so I’m going to try to bring in more perspectives than is feasible in a media-standard 700-word commentary.

As quick recap, the agreement is to allow 49,000 EVs from China per year (rising to 70,000) to arrive in Canada under a nominal import tariff (6.1%). Half of these will have to be priced at under CAD $35,000 (so … $34,999? 😅 ). In return, Canada wants some production from those Chinese companies to be localized.

In no particular order:

Auto Workers: the Achilles’ heel of climate commentary for general audiences is that many writers jump straight into climate impacts before they talk about jobs and workers (or job losses). More people will always be more worried about making ends meet (including having employment) than worried about the climate. It’s a Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs thing.

If conservatives focus on jobs while progressives focus on the environment, progressives won’t like the election results. This even applies to BC’s LNG efforts. It’s a tough ask for most communities to turn down economic activity. It’s easy to say they should turn it down if your income doesn’t dependent on it.

So, I want to start with auto workers. I think this early agreement is the best possible outcome for Canada’s auto workers. Auto companies won’t like it – no one likes more competition – but there’s now a carrot-and-stick to encourage Chinese automakers to put roots down here.

In hockey terms, you don’t skate to where the puck is, you skate to where the puck is going. Electrification is the future of autos – where autos are going – and China is the leader in electrification. All the more reason to try to bring them in.[2] In one sentence, even if today’s auto companies flounder decades from now, tomorrow’s auto workers can flourish. That’s the lesson from the Japan Two.

But first, a quick thought about agriculture.

Agriculture: China had the upper hand in these negotiations. That’s probably to be expected when middle powers negotiate with great powers. While Canada will open its auto market a little bit, the framing of early reports is that we expect China will reduce or eliminate tariffs on various food goods. That should be good farmers and potentially fishers, though if we had more leverage maybe we could have bargained for more.

The Japan Two: like many industries facing competition from lower-cost regions, Canadian auto sector production has dropped about one-third in the past decade from about 2.2 million vehicles per year (2015) to about 1.4 million (2024).[3]

Production at Toyota and Honda has been steady; the losses have come from the Big Three. Those losses are how the Japan Two went from about 45 percent to about 75 percent of Canadian auto production in the past decade, without building new factories. Their arrival wasn’t good for the incumbent auto companies – the Big Three – but has proven to be good for auto workers.

Toyota and Honda first set up in Canada in the 1980s, so in 40 years Japanese carmakers went from an existential threat to our biggest producers. The Canadian government wants to use the same strategy with the emerging Chinese auto giants: “If you can’t beat ’em, make ‘em join you”.

Forwarded this essay? Enjoying it? Subscribe to Eclectic Lip for more!

There are some differences – history doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes – and data tracking is being cited as a reason to stay away from Chinese-made cars. I don’t think that’ll stay a concern for long.

A columnist for the right-wing National Post recently wrote about the plausibility that US government agencies could/would support Alberta separatists, and a few days later the US Treasury Secretary talked up the idea of an independent or part-of-the-US Alberta.[4] [5]

We’re probably at or nearing the point where many Canadian car buyers would rather their data be sent back to China than data to the US. To borrow from Muhammad Ali, “no [Chinese leader] ever called me [the 24th Province].”

China One? It’s been reported that BYD and Chery met with Canadian trade representatives recently, and Chery is known to have had plans to set up in the United States. Perhaps they’ll be among the Chinese automakers (OEMs) angling for a slice of those 49,000 vehicles.

It might not just be Chinese OEMs: western, Japanese and Korean brands also make EVs there. Before the American and Canadian governments put a 100% surtax on Chinese-manufactured EV exports, many Tesla’s imported into Canada had been assembled in China. Given China’s state-supported capitalism, however, we would expect those 49,000 vehicles to be allocated to Chinese brands.

The preferred minimum size for a passenger auto plant is 200,000 vehicles per year, and about 18 million autos are sold in North American each year. So, an automaker would only have to capture 1 percent of the market to make things work.

Unfortunately, we can no longer assume frictionless access to US car buyers, and the Canadian market is only about 2 million vehicles a year. To keep production lines humming Chinese automakers setting up here would probably ship some of those cars to Europe (13 million). A more detailed industrial policy outlining steps and safeguards is expected in February.

Whatever models Chinese OEMs sell or make here, they probably won’t be super small and super cheap, partly because…

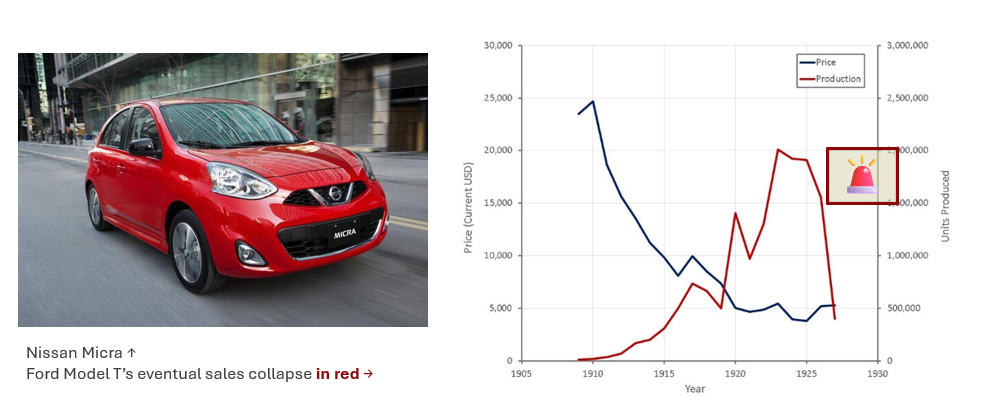

Cheap Cars Don’t Always Sell: some have forgotten, and most have never known, that from roughly 2014 to 2019 Canadians could buy a $9998 car, the Nissan Micra. It’s no longer available in Canada – it sold adequately, not splendidly – but continues to be offered in Europe, now as a battery-electric version.[6]

Adjusted for inflation, that’s roughly CAD $12,000 at time of writing (2026).

The Micra (known as the Nissan March internationally) was never sold in America – Americans don’t buy small cars – but that 2014 pricing was about USD $9000 at the time.

I mention the Nissan Micra because it teaches us a lesson – inexpensive bare-bones cars don’t sell well, if most people can afford something a little bit more expensive. Sales of the almighty Model T Ford collapsed in the 1920s, partly because as soon as car buyers could afford a fancier car, they wanted a fancier car.

Happily, Chinese EVs imported to Canada are more likely to be in the “cheaper but fancy enough” bucket. It costs money for a brand to set itself up in a new market; it needs profits to make themselves whole. And a company can make more profit on a $35,000 car than a $25,000 car: all the more reason to expect the affordable EVs to be priced near the former level. Happily, cars at those price levels should be fancy enough; they shouldn’t suffer the Micra or Model T’s fate.

Automakers: neither incumbent companies nor their industry associations like competition. This isn’t a matter of “greedy industry” either; if new environmental non-profits show up and compete with existing non-profits for the same-sized pool of funding and foundation grants, those incumbents wouldn’t be pleased either. It’s an unforced error to attribute the worst to people on the other side of the table.

There has also been a lot of ZEV policy and incentive tinkering in the past decade, and constantly shifting regulations are among the last things a capital intensive, low margin business would want.

Nonetheless, the greater good of competition is that it benefits more-numerous consumers at the expense of less-numerous producers. When I was growing up, the American and Japanese car markets were a case in point.

The United States had three automakers. In retrospect that wasn’t enough for strenuous competition. Japan had eight: Toyota, Honda, Nissan, Daihatsu, Suzuki, Mazda, Mitsubishi and Subaru. With that much competition, no one could afford to get complacent! On the other hand, with that much competition only the biggest three (Toyota, Honda, Nissan) have the resources to develop EV platforms.

Adjusting for population, Japan’s eight carmakers would be like the United States having 25 competing, profitable car companies – or China having 100. (China is widely estimated to have about 200 automakers, almost all unprofitable.)

It probably isn’t sustainable for any country to have dozens of carmakers – not even China – but if we replayed history and General Motors wasn’t allowed to buy quite as many competitors a hundred years ago, North America might have had more automakers and more intense competition. Brands they acquired included Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Cadillac … and Oshawa, Canada-based McLaughlin Motors!

Net-net: Turning back to workers, giving Chinese manufacturers access would be a slam-dunk if Canada didn’t have an auto sector. Since we do have an auto sector – and it’s an important one – offering some access (win for consumers) in return for some assembly (win for workers) feels like the right choice. The fine details will make the difference between a net win and a net loss, but a winning outcome remains in play.

Enjoying commentary rooted in empathy? Subscribe here to receive future essays in your email inbox!

[1] Chrysler’s gone through a few name changes over the decades. Once upon a time we might have said that Chrysler begat DaimlerChrysler which begat Chrysler which begat Fiat Chrysler which begat Stellantis.

[2] If you think back to high school biology, Canada bringing in Chinese automakers would be like how “eukaryotic” cells first incorporated mitochondria, to mutual benefit.

[3] https://www.cvma.ca/industry/stats/

[4] https://nationalpost.com/opinion/john-ivison-maga-has-its-sights-on-alberta

[5] https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/trump-cabinet-member-weighs-in-on-alberta-separatism-9.7058082

[6] https://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-drive/reviews/new-cars/nissan-micra-is-canadas-teeny-car-with-the-tiny-price-a-big-bargain/article18776746