Beethoven's Notes, Medical Diagnoses and Motorcycle Maintenance

In my irrepressible nerdiness I finished this scholarly book on Christianity recently, which illuminated the importance of the context of written words. Especially hallowed words which influence culture.

The gentlest way to ease into this is through Beethoven’s 9th Symphony and Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance before getting into the heavier stuff, so here we go!

Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, familiar from Die Hard, finishes with a soaring chorus. But it can be a slog, especially at the start of the fourth movement, which is … noisy.

It’s more enjoyable when you realize Beethoven has reintroduced – then rejected – the themes from the first three movements (“not good enough for the finale!”). After those rejections, the theme of the fourth movement begins in earnest. Knowing what Beethoven’s doing helps you understand the structure underpinning that brief cacophony.

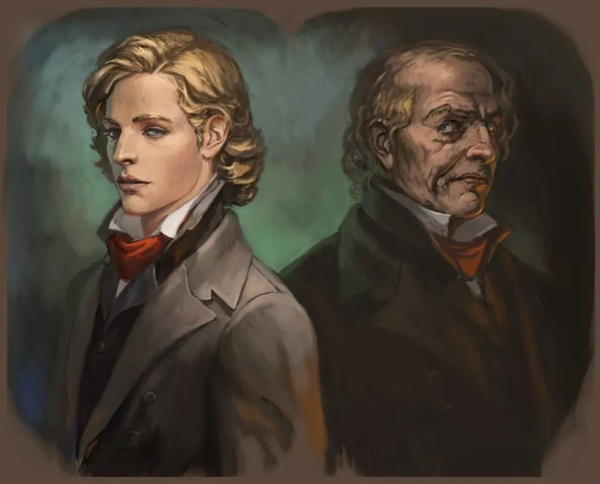

I’ve read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance many times, and for several years described it as a great book with a bad ending. Not “Game of Thrones” bad, but still unworthy of the rest of the book. That all changed with the 25th anniversary edition, where the publisher let Pirsig fiddle with the fonts to visually signal a change in narrator.

All along the story had been told by the author’s post-electroshock therapy personality, whom the son is distant from. At the very end, the pre-electroshock personality regains the upper hand; the son recognizes his (original) father is speaking; and the ending is uplifting. Soaring, even.

Nothing in any edition of the book until that point indicated the change-in-narrator, which – as Pirsig noted in the anniversary edition – confused countless readers. Who wrote to him. To get an explanation.

Visually signalling to the reader that the last passages should be read differently, made all the difference.

Easing into religion with Buddhism, the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths are kind of abstract, like any generic list.

But once you know they follow the format of then-contemporary doctors’ diagnoses, you get insight about how the earliest Buddhists wanted to represent their faith: as the spiritual equivalent of medicine. And that’s why the nucleus of Buddhist teaching has the structure of “there is a problem; it has a cause; it has a cure; do XYZ to be cured."

So, main-event time. 🛎️🔨

The 23rd of 27 documents in the Christian New Testament is the First Letter of John (“1 John”). It’s not a long read – all of five chapters – but it’s not the easiest read either.

David Trobisch, the well-respected scholar who wrote that book I mentioned earlier, suggested reading it as a letter which a proactive editor has rounded out with supplemental commentary. Which was written in a very different writing style. And interrupts the flow. This was 1500 years before the invention of punctuation, so perhaps the author/editor distinctions were conveyed verbally … until they weren’t.

When we (temporarily) set aside passages by that editor – not implausibly Polycarp of Smyrna – to see how the source text flowed, its original voice sings through. And regardless of our religious disposition, we can read the tenderness with which the original author (officially, the apostle John) wrote:

"My little children, I am writing these things to you so that you may not sin. Beloved, I am writing you no new commandment, but an old commandment that you have had from the beginning. Yet I am writing you a new commandment that is true in him and in you, because the darkness is passing away and the true light is already shining.

I am writing to you, dear children…”

Which appreciation we only have once we add context to the text of the words we’re reading. 😊

If you liked this, please send to a friend, and/or subscribe! 🙏